20090803

6page/ 막장드라마를 더이상 환영하지 않는 이유

‘막장드라마’를 더이상 환영하지 않는 이유

정은영/작가

문제 하나. 믿을 수 없는 시청률을 거듭 갱신하다 지금은 종영한 막장드라마의 최고봉 ‘아내의 유혹’의 주인공 구은재와 신애리의 차이점은? 답은, 별 차이점이 없다. 는 것. 이 두명의 여자는 어디서든 수가 틀리면 제 물건이건 넘의 물건이건 홀라당 내리쳐버리는 것으로 요란한 등장을 알린다. 타인의 고통따위는 안중에도 없고, 오로지 자신이 얻어낸 것을 빼앗기지 않기 위해서 악다구니를 할 뿐이다. 목표달성을 위해서라면 그 누구와도 야합하는 건 막장드라마 히로인들의 기본이다. 깡패든, 배신한 옛애인이든, 과거의 동지든, 적이든, 누구든. 성공적이면 전선이 수립되고, 실패하면 등을 돌리거나 복수하면 그만이다. 모든 모략과 음해의 중심에는, IT와 모바일 산업의 메카인 대한민국답게도 휴대폰이 있다. 그들은 늘 신상 휴대폰을 이용해 상대의 등에 칼을 내리 꼿기 위한 문자, 이미지, 음성, 영상 등을 자유자재로 날리고, 그럴때마다 그들사이의 긴장은 서늘하리만치 팽팽해 진다. ‘자본’을 가지고 노는 수위는 또한 어떠한가? 나같은 무명의 예술가들은 아마도 죽는 그 날까지 구경하기도 힘들 액수인 몇십억대 돈이 늘 아무렇지도 않게 거래된다. 그들 마음속 깊은 곳에 자리한 상처와 피해의식, 그리고 그것을 넘어서기 위한 서슬퍼런 복수의 칼날은 항상 거침이 없다. 그들이 이토록 악다구니를 부리며 ‘살아 남아야만’ 하는 이유는 결국은 ‘상처의 치유’라는 당위로 가장한 자기욕망의 한계점을 더이상 컨트롤 할 수 없는 상황에 이르렀기 때문이다.

나와 한 친구는 전 인류의 ‘아유(아내의유혹)’화를 통탄하며 우리 시대를 진심으로 걱정하는 마음으로(!) 드라마를 애청했었다. 하루가 멀다하고 벌어지는 음해전술이 업글에 업글을 거듭할수록, 그들의 악다구니가 극에 달하면 달할수록, 거래되는 돈의 액수가 커지면 커질 수록, 그들의 불안함과 두려움 또한 최고조에 달하는 극적긴장은 실은 우리가 마주한 세상과 비교해보아도 전혀 다를바가 없었던 것이다. ‘막장드라마’는 우리에게 종영을 약속해 주지만, ‘막장시대’는 대체 언제 종결 되는 것인지 전혀 예측할 수 없었기 때문에 우리는 드라마를 보면서도 슬펐다. 개인의 일상과 삶을 멈추고 쉼없이 촛불을 들어도, 일하기를 원하는 이들이 자신들의 일터를 빼앗겨야만 해도, 자신의 주거지로 부터 내쫓기거나, 생존을 요구했을 뿐인 이들이 난데없이 화염에 휩싸여도, 혹은 그렇게 개혁의 역사를 원했던 전직 대통령의 ‘자살’이 모두를 충격과 비탄속에 몰아넣어도, 철저하게 신애리이며 구은재인 누군가의 모략은 수위를 높혀가기만 했다. 남한의 전 대통령 서거에 조전을 보내자마자 핵실험에 돌입한 북한의 도발은 막장대본을 더욱 막장으로 만들기 위해 ‘부활한’ 민소희의 귀환쯤일지도 모르겠다. 물론, 민소희 역시 신애리, 구은재의 판박이같은 존재다. 이쯤에서 던지는 또다른 문제하나. 이명박과 김정일의 차이는? 막장드라마의 충실함은 이 질문에 답을 하는 순간 다시 시작될 것 같다.

The Narrow Sorrow: 삶에의 경의, 죽음에의 애도/2009베니스 비엔날레 한국관 출판물 (양혜규: Condensation)

정은영 siren eun young jung

누가 인간으로 간주되는가, 누구의 삶이 삶으로 간주되는가…무엇이 애도할 만한 삶으로 중요한가. 1

동두천2 을 배회하던 유난히 뜨겁던 어느 여름의 한 낮, 나는 “누구의 삶이 삶이며, 어떤 삶이 애도할만큼 중요한 삶인가”라는 버틀러의 질문을 떠올리고 있었다. 원주민을 밀어내고 거대하게 담장을 친, 미군 기지를 중심으로 조성된 남한의 이 작은 ‘군사 도시’의 시가지를 배회하며 마주치는 얼굴들은, 주로 이주민이라 호명되는 다양한 인종들이다. 거리를 활보하는 이국의 여자들은 아기를 눕힌 유모차를 밀고 나와 삼삼오오 한 낮의 수다를 즐기는 중이고, 골목골목마다 이국의 언어가 자연스레 들려온다. 미군들의 나잇 라이프와 여흥을 돕는 클럽의 수 만큼, 이국에서 온 여자들의 수가 넘쳐나고, 이국 음식점과 식재료를 파는 상점들 또한 넘쳐난다. 오래 전, 클럽에서 일하던 여자들의 시체를 흘려보내던 신천3은 이제 그 주변을 시민공원으로 단장하고 미군과 클럽여성의 낭만적 데이트를 위한 장소를 제공한다. 반짝이는 수면과 녹음이 어우러진 여름의 냇가는 여자들의 시체를 흘려보내야만 했던 비정의 역사를 더 이상 상기시키지는 않는다.

캠프케이시Camp Casey 4 근처의 보산동 클럽가는 형형색색의 촌스럽고 요란한 건물 외관과 간판들이 무색하게도 너무나 적막하여 어떤 숭고함 마저 느끼게 한다. 가끔, 낯선 인물인 나의 등장이 이 골목에서 삶을 영위하는 사람들에게 불편할 수 있다는 것을 눈치채는 것은 그리 어렵지 않다. 나를 발견한 사람들의 몇몇 질문과 공연한 시비가 간간히 이 골목의 적막을 깬다. 그들은 아주 옛날, 그들의 조상들이 그랬던 것 처럼 농사를 짓지 않는다. 그들은 거의 미군을 위한 서비스업에 종사하며 삶을 살아간다. 나는 본의 아니게 그들의 삶의 공간에 침범한 침입자가 되고 만다. 밀려드는 죄책감을 애써 숨기며 능청스레 그들을 상대한다. 그리고 최대한 예의를 갖추어 묻는다. “이 지역이 곧 개발된다고 해서 보러 왔는데, 언제 된다던가요?” “그런 소리 마, 내가 여기서 몇십년째를 사는데, 그런 일은 없을 것 같소.” “미군도 곧 빠진다던데요?” “ 허이구, 그 소리를 벌써 십수년째 듣는데.. 아니야.” 전국 곳곳의 개발지역이 신자유주의자들의 자본우선 논리로 모든 것을 밀어내고 개발 ‘병’을 앓고 있는 반면, 이곳의 개발은 미군의 전세계적인 군사 재배치 ‘이후’의 문제가 될 것이다.

군부대 안으로 들어가는 것은 물론 금지되어 있다. 일반인에게 오픈한다고 알려진 날 소정의 절차를 밟았으나, 그들은 한순간에 말을 바꿔 동두천 지역 외 거주민의 견학을 허락하지 않았었다. 군인들이 드나드는 입구의 근처까지 바짝 다가가 문 너머를 기웃거린다. 사실 무엇이 저 문 너머에 펼쳐지는가를 궁금해 하는 것은 아니다. 공주봉 에 올라서서 바라봤던 캠프 케이시의 전경은 그야말로 하나의 이상적인 근대 도시와도 같았다. 합리적으로 구획된 블럭들과 잘 닦여진 도로, 적절하게 어우러진 녹지가 안정감을 자아내던 것을 기억한다. 최근 캠프 케이시 주변의 골목들은 도시가스 공사가 한창인데, 담장을 사이에 두고 부대 안쪽과 바깥쪽의 편의시설이 이렇게 차이가 날 수 있다는 것이 너무나 비현실 적으로 느껴진다. 담장을 따라 걸으며 생각에 잠기다가 다시 골목을 배회한다. 건물의 배치와 구조들이 일반적인 도시의 풍경을 연상시키지는 않는다. 공간의 모습은 늘 그곳에서 삶을 영위하는 사람들의 삶의 양식을 그대로 현현한다. 경계의 삶, 틈새의 삶, 등록되지 않은 삶, 뿌리내리지 않는 삶. 그 삶이 현전하는 장소들은 번지없이 잘게 나뉘어 정주민들이 버려둔, 잉여로 남겨둔 공간을 메운다.

상패동의 무연고 공동묘지5는 6-70년대 남한의 근대적 욕망의 군사화와 그 트라우마를 고스란히 안고있는 ‘유령’들의 장소다. 최초의 반환 기지인 캠프님블Camp Nimble 6을 끼고 도로변을 한참 걷다보면 울룩불룩 묘지들의 형체가 어렴풋이 드러나는 작은 동산이 보인다. 한 여름의 잡초들은 무섭도록 빠르게 자라나는 탓에 묘지로 올라가는 길은 막혀 있었다. 여러차례 기어오르기를 시도했지만 나지막한 동산인데도 올라설 수 없을 정도로 무성하게 뒤덮혀 버린 것이다. 얼핏 잡초들 사이로 보이는 검은 말뚝들이 번호를 달고 있을 뿐, 이 곳에 묻힌 이들에 대한 어떤 정보도 찾아 낼 수 없다. 어떤이들의 죽음은 너무 빠르게 잊혀지고, 한여름의 잡초는 너무 빠르게 자란다. 묘소에 오르기를 포기하고 내려오면서 동산 초입의 작은 냇가를 새삼 발견한다. 본래 물이 흐르는 곳에 묫자리를 쓰지 않는다는 풍수지리의 전통적 지혜를 무시한 채 물길이 이 작은 동산을 따라 흐르고 있는 것이다. 냇물이 흐르는 소리가 오히려 어떤 ‘언어’처럼 느껴질 지경이다. 물소리에 귀를 기울이며 잠시 그들을 위해 묵념한다.

어둠이 내려 앉으면 보산동의 클럽가는 한낮의 침묵을 잊고 떠들썩해 진다. 번쩍이는 네온과 소란스러운 음악, 여자들의 웃음소리, 남자들의 허세와 고함이 여름공기의 습한 기운을 타고, 이국음식들의 향기와 술냄새, 그리고 ‘어떤’ 비 가시성들이 뒤섞여 흐른다. 미군들, 카투사들, 상점주들, 클럽주들, 마마상들, 클럽의 여자들, 상점의 점원들, 배회하는 거리의 구경꾼들과 보행자들. 다채롭기 이를데 없는 인종, 젠더, 권력, 국적, 직업, 정체성의 혼란한 뒤섞임들 속에서 나는 철저하게 이방인으로 위치지어 짐에도, 이들의 삶에 강한 연대감을 느끼고 있다. 낮에 들렀던 필리핀 이주여성들을 위한 작은 공동체 미사에서 내 마음을 사로잡았던 타갈로어의 신성한 음성들이 이 거리의 떠들썩한 소음과 조화를 이루어 내는 것을 상상한다. 성스러운 종교적 언어들이 이곳의 저열하고 취약하며 세속적인 언어들과 리듬의 조각을 하나씩 맞추어 가는 것을 상상하는 것이다. 이 ‘벌거벗은 삶’ 의 내부를 채워나가는 동시에, 우리의 눈앞에 펼쳐진 삶의 장소들을 촘촘히 메우고 있는 숨쉬는 언어들이 지금 이 기이한 여름밤의 공기들처럼 엄연히 우리에게 감지된다.

우리는

반짝거리는 것들에

온통

마음을 빼앗겨 버리고 만다네.

반짝이는 네온과 간판,

반짝이는 여자들의 드레스와 장신구,

반짝이는 조명이 돌아가는 반짝이는 무대,

반짝이는 유리잔을 든 반짝거리는 손톱,

반짝이는 아이섀도우 아래의 반짝거리는 검은 눈동자,

반짝이는 뾰족한 하이힐이 반짝이는 바닥위를 톡톡 구르는,

반짝거리는 것들로 가득한 그 도시에선

여자들의 웃음소리마저 반짝이는 보석처럼 아름다웠지.

반짝, 반짝, 반짝,

반짝이는 것들을 사랑하는

우리는

그 빛나는 아름다움을 쫓아

그 곳으로 갔다네.

모든 것이 시시해지는 어두운 밤에도

그 도시는 더욱더 아름답게 반짝거렸으며

여자들의 웃음소리는 밤하늘의 별보다도 아름다웠지.

We are

Completely

Entranced by

Twinkling things.

Twinkling neon lights and signs,

Twinkling ladies’ dresses and accessories,

Twinkling stage where twinkling lights twirl around endlessly,

Twinkling fingernails holing a twinkling glass,

Twinkling black eyes underneath the twinkling eye shadow,

Twinkling pointed high heels tapping buoyantly on the twinkling floor,

In that city brimming with twinkling things,

Even the ladies’ laughter was enticing like twinkling gems.

Twinkle, twinkle, twinkle,

All of us,

Who loved twinkling things,

Went there,

Chasing after that glittering beauty.

Even during nights when everything becomes dull

That city twinkled more and more

And the ladies’ laughter was more beautiful than the stars of the night sky.

누가 인간으로 간주되는가? 누구의 삶이 삶으로 간주되는가? 무엇이 애도할 만한 삶이고, 무엇이 그렇지 않은가? 나는 이 거리를 빠져나오며 다시금 질문을 반복한다. 존재하면서도 존재하지 않는, 살아있으면서도 죽은, 버틀러 식으로 말하자면 ‘구성적 외부’인, 아감벤식으로 말하자면 ‘호모사케르Homo Sacer’인 이들의 삶과 죽음은 어떻게 애도받을 수 있을까? 나는 페미니스트 예술가로서, 다시 한번 주권의 밖에 있는 비체적 개인들의 정치성을 재현하리라 마음먹는다. 이 도시의 역사와 그 풍경을 가로지르면서, 그리고 그 공간을 메꾸고 있는 삶의 공기를 나누어 마시면서 삶에 대한 경의와 죽음에 대한 애도를 표해야 함을 강하게 받아들인다. 삶과 죽음이 위계화 될 수 있다는 사실을 늘 목격하고 경험하면서도, 우리는 누구나 평등하게 삶을 상실할 것이라는 사실을 또한 알고 있다. 언젠가는 나 스스로가, 사랑하는 사람들이, 이웃이, 또는 한번도 본적이 없는 사람들이 사라질 것이라는 이해가, 우리에게 어떤 ‘공공의 영역’, 혹은 ‘공동체’의 가능성 7 을 이 도시안으로 불러들인다.

건물과 건물, 혹은 클럽과 클럽 사이에 존재하는 기이하게도 '좁은' 문 뒤편에는 여자들의 방으로 이어지는 길이 있다 . 이 문의 폭은 너무나 좁아서, 실상 사람이 통과 할 수 있는 문이라 상상하기는 힘들다. 공공의 기억 Public Memory 은 바로 이 같은 비좁은 공간들을 삭제하고, 이곳을 채우고 있는 여자들의 몸 또한 삭제해내면서 선택적 기억의 서사를 만들어 간다. 여자들은 존재하나 존재할 수 없으며, 살아있는 육신으로 현현되나 생존하는 자로 등록되지 않는다. 이들의 말은 쉴새 없이 들려오지만 기입되지 않고 , 수행 Perform은 지속되지만 축적되지 않는다. 이 호모사커 Homo Sacer 들은 좁은 문 뒤편에 몸을 감추고 침묵한다. 무거운 침묵이 이 고요한 대낮의 풍경 속에서 슬픔을 불러낸다 . 삶은, 생존은 어디에 있는 것인지를 물어보지만 아무런 응답도 돌아오지 않는다. 이제 얼마간의 시간이 지나면 천박한 네온들로 휘황찬란한 밤의 거리가 이 침묵과 슬픔을 잠시간 밀어낼 것이다. 소란함 , 유흥, 쾌락, 비천함과 광기로 뒤범벅된 공간이 밤의 시간을 점령할 때, 여자들은 자신이 가지고 있는 가장 화려한 옷을 입고 요란한 말들을 지껄이며 거리로 밀려나와 이 떠들썩한 공간을 또한 점령할 것이다. 이토록 소란하기 짝이 없는 여자들의 목소리가 뒤엉키고, 알아들을 수 없는 소음 덩어리들이 증식을 시작하면, 슬픔은 제 부피를 한껏 줄이고 줄여 비좁은 문의 뒤편으로 사라질 지도 모를 일이다 .

Behind peculiarly narrow gates situated between club buildings, there lies a path leading to even smaller doors of the club workers' shabby lodgings. The width of the gates is so narrow that it's difficult to imagine a person can actually pass through them. Public memory is constructed from a selective narrative of memory, deleting narrow spaces like these and erasing women's bodies that fill these spaces. These women do exist, but they cannot exist; they live as beings with physical presence, but they're not registered as live beings. Their words are heard incessantly, but they're not recorded. Their performances continue but aren't accounted for. They are Homo Sacer who remain silent with their bodies hidden behind the narrow gates. The heavy silence calls forth sorrow from the quiet midday landscape. It questions where life is and what survival means, with no answers returned. After a few hours, glittering night streets with vulgar neon signs will drive out their silence and sorrow, but only for a while. When a site mingled with bustling activity, entertainment, desire, cheapness and madness occupy the night, women dressed up in their most extravagant clothes, chattering in different languages, come out to the streets and proclaim this noisy site as their own. As the women's clamorous voices blend together and the incomprehensible mass of noises increases, the sorrow recedes as much as it can, to possibly vanish again behind the narrow gates.

2. 남한의 경기도 최북단에 있는 면적 95.66 ㎢, 인구 90,000여명의 도시로, 북동쪽으로 포천시, 서쪽과 남쪽으로 양주시, 북서쪽은 연천군에 접한다. 군사보호구역에 속하며, 6·25전쟁 이후 급격히 발전한 기지촌(基地村)이다. (네이버 백과사전 참조 http://100.naver.com)

3. 경기도 양주시, 동두천시, 포천시, 연천군, 파주시 5개 시·군을 가로지르는 지방2급 하천으로 ‘한탄강’으로 흘러 들어가는 지천이다. ‘한탄강’은 본래 은하수 모양의 아름답고 큰 물길이라는 의미를 가지고 있으나, 한국 전쟁 이후 한탄강을 따라 남북 분단이 이루어졌고, 남, 북의 큰 접전이 한탄강에서 자주 일어난 때문에 한과 탄식이 서린 강이라고 불리우기도 한다. (네이버 지식인 참조 http://kin.naver.com)

4. 동두천시에 있는 미군 2보병사단의 기지중 하나. 동두천 전체 크기의 3분의 1의 면적을 차지한다. (위키피디아 참조 http://ko.wikipedia.org)

5. 동두천시에 위치한 소요산의 한 봉우리. 공주봉에 서면 동두천시의 지형을 한눈에 담을 수 있다. 마치 구글 어쓰로 들여다 본 세계처럼 캠프케이시의 전경이 한눈에 들어온다.

6. 캠프님블은 동두천의 기지들 중 미군이 철수하고 그 영토를 대한민국에 반환한 첫 기지이다. 그러나 미군은 이 땅의 소유주로서 공시지가를 적용해 남한정부에 되팔았을 뿐이고 이전비용까지 받아내었다. 2007년 1월 17일 국방부와 환경관리공단은 캠프님블을 처음으로 일반에게 공개하고, 환경 오염도 조사결과를 발표하며 개발을 암시했다. 오염사실이 없다고 주장한 정부의 결과발표에 의구심을 품은 동두천 시민연대는 거세게 항의하며 포크레인으로 땅을 파보았고, 육안으로도 확인가능한 심각한 토질오염 상태를 확인했으며, 국방부와 환경관리 공단의 관계자는 시민연대의 이러한 개입에 난색을 표하며 이 자리에서 약간의 긴장과 몸싸움이 일어났다. 이날, 한국전쟁 이후 미군부대에 자신의 농지를 빼앗긴 한명의 원소유자의 가족들도 이 광경을 보고 있었다.

7. 모리스 블랑쇼/장 뤽 낭시, 밝힐 수 없는 공동체/마주한 공동체, 박준상 옮김, 문학과 지성사, 2005 를 참조

동두천프로젝트를 마치며/ BOL009

동두천 프로젝트를 마치며/정은영

지역연구에 베이스를 둔 미술프로젝트를 진행 한다는 것은 애초에 나에겐 큰 도전이었다. 거의 모든 시간을 방구석에 틀어박혀 오로지 스스로의 의지박약과의 지난한 싸움을 번번히 일삼으며 침묵속에서 작품들을 생산해 왔던 일천한 경험은 그리 내세울만한 것이 아니었다. 나는“예술가”라기보다는 “활동가”로서 움직여야 할 것이 뻔한 이 프로젝트에서의 나의 자격을 의심할 수 밖에 없었다. 또한 이러한 종류의 프로젝트를 진행/수행하는 대부분의 작가들에게 가장 큰 딜레마일 것이라 짐작해 마지않는 ‘개입’과 ‘침입’의 경계설정의 문제, 또한 예술가와 활동가라는 정체성을 내적으로 통합해야만 하는 과제, 더불어 ‘재현’이 곧 ‘대표’가 되어버리는 이데올로기적 음모를 어떻게 유유히 뚫고 새로운 언어들을 솟아나게 할 수 있을 것인가 하는 질문까지 이 모든 문제들이 한껏 내 어깨를 짓누르곤 했다.

리서치라는 명목으로 허구헌날 동두천을 드나들었지만 사실 외지인인 내가 어떻게 이 공간의 ‘지역성’과 그곳에서 삶을 영위하는 ‘지역민’이라는 울타리를 훼손하지 않으면서도 이 모든 삶의 편편들에 가까이 다가가고 또 어떻게 확장시킬 수 있는가에 대한 답은 아직 얻지 못하였다. 답을 얻기는 커녕, 나의 작업이 한명의 ‘외지인’에 불과한 누군가의 부박한 관찰기가 되는 것 만은 막아야 한다는 무척 소심한 목표를 여전히 되새김질 하고 있을 뿐이다. 이미 이년여간의 프로젝트 진행과정을 마치고 세차례의 전시를 끝낸 지금에도 이런 생각을 하고 있다는 것이 참으로 부끄럽기만 하다.

그럼에도 불구하고 동두천 프로젝트는 나에게 여전히 의미있고 중대한 사안들을 제시해왔다. 나는 이 프로젝트를 통해서 다시 한번 미시담론과 미시역사의 정치성을 확인하고, 근대적 기획과 선택적 기억들을 빗겨나면서 독자적으로 존재하며 사라져간 ‘비체’들을 애도하고 그들의 고통에 연대하는 법을 배울 수 있었다. 동두천은 지구상에 존재하는 무수한 도시들 중의 하나에 불과하지만, 그 어떤 지역보다도 ‘전지구적 질서’와 ‘국민국가적 가치’가 거세게 경합하는 동시에 공모하는 신자유주의의 은밀한 기획을 깊고 넓게 들여다 볼 수 있게 해주었다. 나는 이 도시의 풍경을 가로지르면서, 그리고 그 공간을 메꾸고 있는 삶의 공기를 나누어 마시면서, 역사와 기억, 국가와 국민, 경제와 자본 그리고 젠더와 계급에 대해 맞닥뜨린 예민한 문제의식들을 결코 놓치지 않으려 애써왔다.

한편, 나는 동두천의 지역민들에게 어떠한 ‘친밀함’으로 다가가는 것을 부득불 지양했었다는 것을 고백하고 싶다. 밀착적인 관계맺기와 부단한 대화(거의 대부분은 인터뷰가 될)의 시도를 통해 가능한 많은 양의 정보를 수집하면서 지역민을 ‘정보원’으로 혼동하고 싶지 않기도 하거니와, 얼마간의 ‘외지인’의 윤리가 있어야 한다는 판단에서이기도 했다. 지나칠 정도의 신중함과 자기검열이 프로젝트의 ‘소극성’을 변명하는 것은 아닌가 하는 고민에 빠지게 만들기도 하지만 말이다. 그러나 업주들과 사이좋게 담소를 나누며 볕좋은 마당에 둘러앉아 고추를 닦는 클럽의 여자들에게, 오전의 상쾌한 강바람을 맞으며 미군의 팔짱을 끼고 신천변을 거닐며 사랑을 속삭이는 그녀들과 유모차 안의 우는 아이를 달래가며 진지하게 자신들의 미사를 신께 바치는 그녀들에게, 지역에 피해가 갈세라 카메라를 둘러메고있는 나를 불러세워 다짜고짜 소리치는 업주들이나, 수상한(?) 외지인의 출현을 감시하는 동네 사람들에게 어떻게 심각한 얼굴로 사진기나 녹음기를 들이대며, 나의 예술적 열정을 앞세워 그들의 일상을 훼손할 수 있단 말인가. 그저 쑥스러운 웃음을 띄며 조심스러운 인사를 건넬 수 밖에. 물론 그것만으로도 나는 충분히 그들에겐 거슬리는 존재였을 것이 분명하지만 말이다.

실은 수차례의 “접촉”과 “관계”에의 실수와 실패들을 경험하면서 나는 지역으로 깊숙히 밀고 들어가기보다는 외지인으로서 위치할 수 있는 아주 경계적인 자리에 나를 세워두었다. 그곳에서는 모두의 확고한 목소리를 들을 수는 없었지만, 아주 작고 사소한 풍경들과 그 풍경을 만들어내는 삶의 구조들이 서서히 선명해졌다. 나는 그것들을 보다 정치精緻/政治하게 드러내는 것으로 동두천과 그곳의 사람들에 대한 이야기를 하기 시작했다. 아마도 이 프로젝트를 진행하는 동안 작가들에게 부여된 일은, 거시적 역사와 그 풍경을 스펙타클하게 재현해 내거나 “동두천”이라는 국민국가의 트라우마를 폭로하는 것이 아니라, 그 모든 외상을 희생자주의와 민족주의로 상쇄하려는 집단적 치유의 전략을 “거절”해야만 하는 또다른 예술적 전략의 생산이었을 것이다.

이년 가까이 매달려 있던 동두천 프로젝트는 그 과정의 치열함과 내적 투쟁을 뒤로하고, 이제는 단정한 갤러리 안에 얼음처럼 갇혀있다. 갤러리 전시에 회의를 가지는 것은 아니다. 화이트 큐브에 대한 지난한 싸움과 분석과 수정과 협상들은 내가 한마디를 더 보탠다고 마침표가 찍힐리는 없다는 것을 잘 안다. 그리고 무엇보다도 나는 이제 많이 '말하고 쓰는'것에 흥미를 가지지 못한다. 다만 지난 시간동안 그 다채로운 순간순간의 사건 혹은 감정과, 이렇게 다양한 레이어의 의미와 사회적 관계들을 모두 다 설명하겠다고 욕심을 부리지 않는 것이 좋을지도 모른다는 생각을 하고 있을 뿐이다. 가슴속이 묵직해 지는 것 만큼 현상과 물질로 내려앉은 것들에 대해 약간의 아쉬움과 안타까움을 숨길 수가 없다. 그러나 아쉬움과 안타까움을 뒤로 하고 현재의 결과물들이 어떠한 연속성을 가져올 수 있는지를 고민하며 또다른 실천의 방식들을 모색하려 한다.

물심양면으로 큰 힘이 되어주셨던 동두천 시민연대와 활동가 분들과 동두천에서 만나고 지나쳤던 주민분들께, 나의 ‘작가적’이기심과 부족함에도 불구하고 늘 날카로운 조언과 힘있는 격려를 보내주었던 김희진 큐레이터에게, 매 순간 순간 자극제가 되어주었고 콜렉티브의 힘을 알게 해준 동료 작가들에게 진심으로 감사의 말을 전하고 싶다.

브라이언홈즈-애인에게서 벗어나는 50가지 방법

50 Ways to Leave Your Lover

July 15, 2008Exit Strategies from Liberal Empire

Sangdon KIM, Discoplan

Along the river bank in the city of Dongducheon, some twenty miles north of Seoul in the Republic of Korea, the artist Sangdon Kim organized a hilarious public performance. Participants were invited to create slingshots, kites, catapults, flying machines – in short, to hurl every imaginable homemade projectile over the rusty razor wire separating them from the recently vacated U.S. base of Camp Nimble. The missiles carried a payload of clover seeds, which in the best of cases could scatter on impact, sprout, flourish, cover the ground and begin remediating the poisoned soil left behind by decades of military occupation. The kids got ready, took aim, failed miserably for the most part, and burst out laughing with each fresh attempt. The adults enjoyed some pointed comments about the hidden costs of the U.S. force relocation plan, and speculated about possible consequences for their city. The video of the event shows moments of collective reflection and heartfelt comic relief – the feeling that you’ve finally got free of something.1

I am an American, and like most, I’m ignorant of what’s done in the name of democracy by the U.S. military. Whether it’s the raw facts of land occupation by sprawling bases, the tangled histories of collaboration with host nations, or the latest plans for the use of these lethal installations, I have everything to learn. When I arrived I didn’t even know the name of Guem-i Yun, and couldn’t imagine that the artistic performance at Camp Nimble was also intended to commemorate the day, fifteen years ago, when this 26-year-old club girl was brutally raped and murdered by Pvt. Kenneth Markle in Dongducheon on October 28, 1992. But I did know that prostitution around American bases in Asia has been a continuous scandal since WWII, and when I was asked to give a lecture on the Dongducheon project, images of neon-drenched R&R districts and men in enormous armored vehicles swirled confusedly to mind. How to approach such an overcharged issue? The inspiration that struck was a 1975 radio hit by Paul Simon, where the singer explains – or rather, has explained to him – that there must be 50 ways to leave your lover. Though it’s all about an ending, you realize something new is also in the works:

You just slip out the back, Jack

Make a new plan, Stan

You don’t need to be coy, Roy

Just get yourself free.

Hop on the bus, Gus

You don’t need to discuss much

Just drop off the key, Lee

And get yourself free.

After eight long years of the Bush administration’s useless wars, I want OUT of the obscene and seemingly endless love affairs between the U.S. and its army, whether in Iraq, Afghanistan, Korea, or in our own country. But despite what the song says, there is so much to discuss, so many questions, which the works in this exhibition also raise. What’s between us, as the 16 Beaver Group asked a group of Korean artists and activists, during a trip to the new American megabase at Pyeongtaek?2What would it take to exit from a sixty-year relationship that has defined the United States no less than the Republic of Korea? Above all, what does it mean to be free in an age of liberal empire?

Little Chicago and the Silver Screen

While walking around Seoul looking at the city’s splendid museums, my guide for a day, Seul Bi Lee, suggested that we try something interesting for lunch. Pude chige, it was called: “troop soup.” I found myself looking into a boiling metal pot full of tofu, udong noodles, sliced-up frankfurter sausages and macaroni. Perhaps it is when you eat something like that, and recognize the familiar tastes among the strange ones, that you start to realize what we’ve really gotten ourselves into, through the mixing of cultures and nations.

During Sangdon Kim’s research into the oral history of Dongducheon, he learned that the troops had nicknames for the local districts, like “Queens,” “Manhattan” and “L.A.” This kind of G.I. banter is familiar, because it’s the staple of novels, stories and Hollywood movies. The older residents Kim interviewed recalled the fantastic cynicism of the early days: camptown life was all about money, whether it was the soldiers selling black-market goods from the PX, the prostitutes and club owners selling sex and whiskey, or the police selling protection. One of the residents recalls the popularity of the cinemas, along with real events that seem to match the detective flicks and gangster fictions:

Around the theater, the soldiers used to sell the “Made in USA’s.” But at that time, people would just take the stuff and run. Lots of murders! The soldiers did a lot of killing, too. It was horrible! … Prostitutes getting killed, soldiers running away… Mother fuckers! Same when the 7th division was here too. Lots of fires and lots of incidents. I mean, they called here “Little Chicago,” with so many incidents! 3

Of course, everyone must eat and money doesn’t grow on trees, but it pours out where people congregate in pursuit of their pleasures. Plus everybody loves the movies. Another thing you learn from Kim’s interviews are rumors about the conversion plans for Dongducheon’s immense American bases – Camp Casey, Camp Hovey, Camp Mobile – which, it’s said, some of the town leaders wanted to turn into giant entertainment complexes with casinos, like “a Korean version of Las Vegas.” Gambling and the latest forms of electronic spectacle would replace the outdated nightclubs. In reality, a massive sporting complex has already been built, destroying part of the Sangpae-dong public cemetery as a step toward a “Free Trade City” of the future. All this appears somehow natural, when you know that after the Second World War, those involved with the geopolitics of the region – American military brass, Washington officials and local elites – made the wager that an influx of billions of defense dollars could save Asia from communism, through epic battles and dramatic armed standoffs, but also through huge procurement contracts with host-country suppliers, untold thousands of clinging cash registers at local businesses, and all kinds of shady under-the-table deals. This is what’s hinted at in the mottoes that Sangdon Kim inscribes on photographs of commonplace environments in Dongducheon: “Don’t tell the truth though it’s cold and you’re starving,” reads one. “Don’t tell the secrets though it’s hot and you’re starving,” replies the other. Everyone is supposed to keep quiet and cover everyone else’s deal.

By documenting oral histories and giving them form and context in exhibitions, artists like Kim are helping make public the close-lipped and contradictory texture of existence that has been woven around the American military deployments in East Asia since the close of the Second World War. The casual conversation of Dongducheon reads like a chapter of transnational history, lived out at intimate scale in people’s daily lives, and reflected in the violent glamor of the silver screen.

-

visit the website of the work

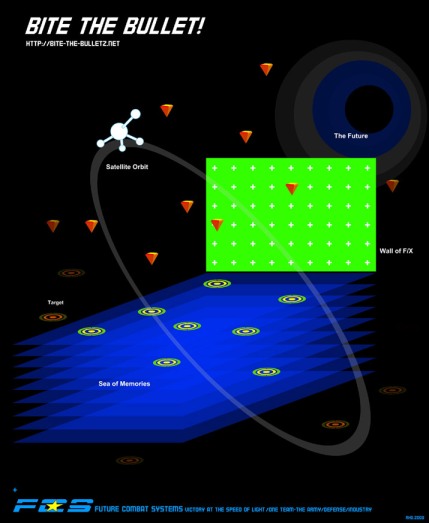

Here is an entry to Roh Jae Oon’s web-based exploration of one of the defining genres of commercial cinema: the war flick. His piece, Bite the Bullet!, is an original interpretation of the spectacle society. Dramatic images of war will be administered as an ersatz anesthetic, distracting the patient from an operation being performed on his or her own body. The 12-part work proceeds by short excerpts, sometimes from two or more films. What’s left out can sometimes be as important as what’s put in. The introductory scenes are from The Bridges at Toko-Ri, a 1954 Hollywood production about a stern admiral, a concerned wing commander, and a reluctant naval reservist flying bombing missions against North Korea. It all begins with love: a woman’s goodbye kiss to her husband departing on an aircraft carrier. What follows is a cut to a sky full of bursting anti-aircraft shells, filmed from the pilot’s perspective; then a shot of bombs destroying a bridge. The movie won an Oscar for its special effects, which are an important focus of Oon’s investigation. But another significant aspect is the famous closing line of the film, which is not included in the excerpt. Reflecting on the discipline that led his pilots to a successful mission and their own deaths, the admiral asks “Where do we get such men?” What exactly is the operation that produces them?

American combat films are about the formation of a national character in battle, a theme played out again and again in Oon’s selections. But what’s at issue in the artwork is also the influence of that process on the population of a client-state engaged in a bitter civil war, elevated to world-historical proportions by Soviet, Chinese and American rivalries. Among the South Korean films that cast their light on the complexities of this relationship is Sang-ok Shin’s 1958 classic, Jiokwha, aka A Flower in Hell, represented with an excerpt from a steamy dancing scene. What casual Western viewers won’t realize, however, is that in the film, these highly erotic sequences are interspersed with others, showing a small-time Korean gang stealing government-issue supplies from the distracted American viewers… Much of the interest and cinephilic pleasure of Bite the Bullet! lies in the ironic combinations that each viewer is free to make, between the scenes that are actually shown and those whose memory is left floating. But this free-floating memory is exactly that condition that Rho Jae Oon sought to encompass in a larger frame. The poster for the piece shows an ellipsoid satellite orbit, a screenlike “wall of F/X” (or special effects) raised bright in the sky, and a deep blue “Sea of Memories” floating down below, on which bull’s-eyes have been meticulously placed, each at its specific level. The implication seems to be that in the networked system of contemporary media distribution, each spectacular bullet can be self-targeted at the memories of individuals, administering what might be called an “anesthetic of one.”

In the last group of excerpts, propaganda images of the US Army’s “Future Combat Systems” confirm the implicit reference to the military-entertainment complex. On a text panel, network-centric warfare guru Art Cebrowski proclaims: “Either you create your future or you become the victim of the future someone creates for you.” Stated by the former director of Donald Rumsfeld’s Office of Force Transformation, which initiated the entire relocation concept that is shifting South Korea’s military geography, that becomes an intensely ironic expression of the high ambition and deep anxiety that the Dongducheon project is trying to communicate to its viewers.

From Militarized Modernity to Liberal Empire

The exhibition looks back at the past without nostalgia or resentment, in order to grasp the complexities of the present and in that way, share at least some hope of shaping the future. Even after considering barely half the pieces, one can sense that each detail and nuance has been discussed intensively during the research process, working to create that most rare of events, a group exhibition (and not just a selection of works to fit a curatorial concept). One can wonder, then, about the absence from the show of a theme that would seem to be central to its whole proposal. I am thinking about the specifically Korean form of productive discipline that Seungsook Moon calls “militarized modernity” – and of the ways that it relates to, and differs from, more characteristically American patterns of character-formation.

Moon describes how a particularly harsh form of discipline, based in large part on practices employed by the Japanese Imperial Army, was generalized to the entire male population of South Korea by means of universal conscription. It was then extended to industrial production through the Military Service Special Cases Law of 1973, which allowed men trained either at vocational at schools or science and engineering institutes to forgo military service for paid employment at defense factories or in heavy and chemical industries. The distinctly gendered male subjectivity that was developed in the military-industrial ranks through the exaltation of masculinity and the parallel denigration of female sex-objects was then reinforced in society by positive images of the man as historical hero and family provider, in contrast to the domestic and subordinated role of women.4

Moon describes how a particularly harsh form of discipline, based in large part on practices employed by the Japanese Imperial Army, was generalized to the entire male population of South Korea by means of universal conscription. It was then extended to industrial production through the Military Service Special Cases Law of 1973, which allowed men trained either at vocational at schools or science and engineering institutes to forgo military service for paid employment at defense factories or in heavy and chemical industries. The distinctly gendered male subjectivity that was developed in the military-industrial ranks through the exaltation of masculinity and the parallel denigration of female sex-objects was then reinforced in society by positive images of the man as historical hero and family provider, in contrast to the domestic and subordinated role of women.4

It would have been important to explore how this this militarized modernity expressed itself in the triple relation between the American occupiers, their ROK allies and local procurers – in every sense of the word – and finally, the male population of the city. To be sure, such subjects were raised by the Minjung painters of the 1980s, with their satirical pop-art vocabularies.5But they are far more difficult to tackle in the living reality of video. The only place in the show where they begin to surface is in the evasive replies of local inhabitants interviewed for Sangdon Kim’s video piece, Foreign Apartment, which inquires into the past functions and current ownership of a ruined white building near Camp Casey, used for prostitution in the 1960s and 70s. Just a few shreds of conversation allow us to imagine the virile discipline of a young Korean man waxing the helicopter of the 7th Division commander who came to oversee the foreign apartment.

-

Sangdon KIM, Foreign Appartment

What remains largely invisible in the show, therefore, is the lived experience of militarized modernity and its consequences on Korean subjectivities today. Rho Jae Oon has perfectly captured the dynamics of this kind of invisibility, but on the American side only. In Bite the Bullet! he presents an audio excerpt from the 1992 courtroom drama A Few Good Men, which he superimposes over touching scenes of a blind woman selling flowers, taken from Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights. On the soundtrack, a hard-bitten Marine colonel from Guantánamo, played by Jack Nicholson, defends his decision to apply deadly punitive force to one of his soldiers, reiterating the classic arguments that every American has heard in a hundred different forms: “Son, we live in a world that has walls… and those walls have to be guarded by men with guns. I have neither the time nor the inclination to explain myself to a man who rises and sleeps under the blanket of the freedom I provide, and then questions the manner in which I provide it!” But his outburst of passion is exactly what allows the young lawyer, played by Tom Cruise, to trick the colonel into admitting his own guilt before the judge.

Here we have the fundamental contradiction that structures liberal empire. On the one hand, a continuous insistence on the imperious necessity of force, to be applied under “states of exception” in distant outposts such as Guantánamo; and on the other, an unshakable confidence in the rule of law, which can always be reestablished back home by the infallible procedures of American democracy. Rho Jae Oon’s ironic superimposition of the blind flower seller onto the courtroom dialogue offers two possible readings of the situation. From the colonel’s point of view, the blindness is obviously that of a sheltered and effeminate civilian world which cannot the face the very force of arms it lives by. But from the post-9/11 viewpoint that is ours today, the blindness lies in the naïve belief that legal instruments can restrain the immense, unbridled powers of the Pentagon.

What are the actual consequences of militarized modernity and liberal empire on our societies today? This is the question that critical artists and intellectuals should never avoid, either in Korea or in America. Take, for example, an intellectual for whom I have tremendous respect: Chalmers Johnson, an American academic, Asia expert and former Cold Warrior, who coined the concept of the “developmental state” in 1982. He had already begun to learn about the secret history of U.S. foreign policy in the library of former CIA director Allen Dulles, while working as a consultant for the National Intelligence Estimate in the late 1960s. However it was only after the fall of the Berlin Wall, when the Cold War ended and American troops did not demobilize but instead remained on their vast array of outposts throughout the world, that he began to revise his views. In 1996, he visited the Japanese island of Okinawa at the request of its governor, Masahide Ota, in order to investigate the rape of a twelve-year old Okinawan girl by two Marines and a Navy seaman. There he began work on another major concept: the “empire of bases.”

More than any other single author, Johnson has revealed the secretive, abusive and fundamentally undemocratic character of U.S. military operations overseas. His latest and best book, entitled Nemesis, warns of the possible end of American democracy, if the CIA’s covert operations, the Pentagon’s secret budgets, and above all, the President’s “executive privilege” are not brought back under civilian control.6But despite all this, Chalmers Johnson has not, to my knowledge, ever revised his positive evaluation of the “developmental state” – a social order that corresponds precisely, in the South Korean case, to the industrial dimension of what Seungsook Moon calls militarized modernity. The question is whether, in the absence of such a reevaluation, one can ever understand the ongoing transition from militarized development in a country like Korea, to the self-contradictory, crisis-ridden regime of liberal empire now extending all over the world.

Johnson has led the way towards a geopolitical understanding of American militarism, by describing the network of over 750 U.S. bases on foreign soil, inhabited by approximately half a million soldiers, support staff, private contractors and dependents, and underwritten by a partially secret budget of approximately a trillion dollars a year. Mark Gillem, an architect working critically inside the U.S. Air Force, takes a further step. His recent study of military urbanism is entitled America Town, in reference to the gated bar and prostitution district constructed outside Kunsan airbase with the active complicity of South Korean officials and businessmen. What Gillem describes in the greatest detail, however, is the “cultural landscape” of contemporary American consumerism as expressed on a plethora of overseas outposts. This is the landscape that the liberalism of open borders and free financial flows has done everything to create, since the heyday of Reagan and Thatcher in the early 1980s. Gillem’s book is invaluable for helping us to understand how that landscape has been structured by the American version of the developmental planning – namely, military expenditure. Take, for example, the description of Kadena airbase in Okinawa, as seen from a viewpoint in a Blackhawk helicopter:

-

The base, with its sprawling subdivisions, strip malls and streets wide enough to land fighter jets, abutted the compact urban fabric of Okinawa-chi, Kadena-cho and Chatan-cho. The golf course stood ready to defend the base at its western edge. The split-level ranch homes had yards big enough to land several Blackhawks. The main shopping center’s parking lot was bigger than the dense town center of Okinawa-chi. What was the U.S. doing building like this in a place so short of land that airports are constructed on artificial islands? How did this happen and what does this tell us about the culture of America’s military and the complicity of the “host” nation? 7

Here, no doubt, are the most concrete subjective consequences of contemporary U.S. imperialism, now being spread across the world by neoliberal economics. What Gillem has assembled is the portrait of a bloated society living on borrowed money and time, under the shadow of current and impending battles for the ultimate developmental resource: the oil needed to run all those grotesquely oversized cars, trucks, ships and planes. The slick, hedonistic world of contemporary hyper-consumerism has brought on the imminent risk of resource wars.8The title of Johnson’s book, Nemesis, expresses this threatening situation very well, with its reference to the Greek deity of vengeance and retribution for hubris, or overweening pride. But how could he have failed to notice that the Nemesis is also the goddess who cursed the proud young man Narcissus, causing him to fall fatally in love with his own reflection?

Pretty Things that Glitter in the Dark

Here’s another question, closer to everyday experience. Is it possible to see through the cheap façades on which the history and the future of our desires are reflected? This is what siren eun young jung has attempted in a video installation entitled The Narrow Sorrow. She begins with a freeze-frame on one of the tiny doorways barring the walk space between two clubs. The passageway leads back to the lodgings of the Filipino girls who are now brought over by the hundreds to work the strip joints and brothels of Dongducheon. Moving images then begin to appear on the various rectangular spaces: first the gate itself, then the façade of the Bridge Club, the sign of the J.C. Beer Bar Lounge, etc. We see street scenes, construction sites, landscapes and rather ghostly images from the Sangpae-dong cemetery, accompanied by an incomprehensible hubbub of voices and muted music. Towards the end of the video, a woman’s body is wrapped in rough cloth for burial. The soundtrack is actually street noise mingled with the organ music from a service in the local Filipino church. The seduction of twinkling lights forms the subject of an elegiac poem that hangs on the wall nearby the installation.

-

siren eun young jung, The Narrow Sorrow

Artistically and politically, The Narrow Sorrow tries to walk through the eye of a needle, groping for a representation of the lives and struggles of women who are doubly excluded from Korean society, because they are sex workers and because they are Filipino immigrants. Yet at the same time, one learns from a scholarly article that the departure of peasant girls from the countryside to the city has left a wife-gap, which is presently being filled by mail-order brides. “By 2004 approximately 27.4 per cent of rural South Korean men were married to non-Korean women.”9Vietnamese women are particularly prized, because of their Confucian heritage. Behind one out of every four rural façades there are messengers from distant worlds.

The work entitled Driveling Mouth, by Koh Seung Wook, explores the destinies of so-called “Western princesses,” who left Korea in the tow of their G.I. husbands and found themselves within four American walls haunted by memories. Their pictures, in glittering party dress, can now be found on Internet homepages. The video installation invites you inside the darkness of a camouflaged tent, where no time is wasted on the niceties. “No matter how hard I work, I couldn’t see a future ahead,” reads a text panel. “I had to become a hooker, and a hooker’s grandma if I could.” The narrative that unfolds is one of marriage and departure, disappointment and bitterness; and then it is told again, with the same pictures symmetrically reversed, from the viewpoint of an Amerasian boy who was abandoned by his father before his birth. At one point we are told that the nameless dead in Sangpae-dong cemetery are called “whores” by some, “Yankee princesses” by others, or “Sisters of the Korean people” by those who resent the violence of the American soldiers. “But what should I call them?” the text asks. “No, why should I even want to call them?” The drivel that pours from two contemporary figures’ mouths seems to embody the obscenity of all those useless words. But it is also the moist inner life of a woman and a man, leaving a wet stain on clean, pressed clothes.

-

KOH Seung Wook, Driveling Mouth

What emerges from the multiple layers of representation in the Dongducheon project is both subtle sociological investigation and an outpouring of intimate expression, bound inseparably together by the challenge of the future. There may well be a clue here for those who are wondering how to definitively move beyond the attitudes of the 1980s generation, when the democracy movement violently confronted the forces of order on the streets, while the Minjung artists excoriated militarist discipline on their canvases. That step beyond is clearly being taken by contemporary Korean activism, which, curiously enough, has also been seduced by pretty things that glitter in the dark. I think it’s worth noting that the first candlelight demonstrations arose in 2003, with the massive protests against American bases after the deaths of Hyo-soon Shin and Mi-sun Shim under the treads of a U.S. Army tank; and that those nation-wide protests came about spontaneously, at the instigation of an inexperienced youth who spread the idea over the Internet. Here, as in the art exhibition, one might point to the cross-class solidarities of an egalitarian feminism, following the arguments of Seungsook Moon who sees a specifically gendered difference in the forms of political engagement developed by women after the end of the dictatorship. But on the basis of my own experiences in Europe and North America, I wonder if the generational question is not equally important. In a deeply flexibilized economy, where mainstream unions can help vote in a conservative president in reaction against the perceived threat of casualized and immigrant workers who are themselves required by the neoliberal policies of that same president, the impossible and unrepresentable struggles of Filipino club girls could be more relevant to the political landscape than any exclusively working-class tradition would allow us to imagine.

In response to my questions about the aims of the recent protests against the importation of American beef – and against the “bulldozer” approach of the new president – the activist and professor of peace studies, Daehoon Lee, replied that in his view “the people are searching for their soul.” The reason why is clear: in the contemporary period, both political adversaries and political goals are hard to name. Driven by the volatile winds of finance, liberal empire is inherently crisis-ridden; and the chaotic swings of its transnational economy can provoke a conservative return to order at any time, as we’ve seen in the most ugly way in the United States. Under these conditions, the claims of democracy and the rule of law can easily collapse into a state of exception. But it is the ordinary, lawful, democratic functioning of liberal empire that provokes the crises, above all when the endless productivism and consumerism of industrial modernity meets its limits and gives rise to resource wars. How a more sustainable form of society can be found is the ultimate question. The search to articulate political subjectivities with a foundation in personal experience and a consciousness that goes far beyond them is what interests me most today. This articulation isn’t easy, and among other things, it involves changing the definition of what art is and what it can be. That’s almost impossible to do when you have repressive regimes on your back. Yet the shaky footing and extraordinarily poor press of militarism in South Korea, and elsewhere in Latin America and Europe, gives some hope that the worst may be avoided, and that more long-term problems may come to the fore again.10

I said at the beginning, quite naively, that I was looking for an exit from liberal empire, and I still am. But beyond the moment of exodus comes a season of new beginnings. Maybe what’s needed to redefine freedom in our time are 50 ways to find your lover.

-

Demonstrations against US bases, Seoul, 2003

NOTES

1 Sangdon Kim’s video document, Discoplan, was presented along with all the other works I will mention here at the exhibition Dongducheon, A Walk to Remember, A Walk to Envision, curated by Heejin Kim at the Insa Art Space in Seoul, July 16-August 24, 2008. It was previously presented at the New Museum, New York, May 8-July 6, 2008.

2 For documentation, see http://www.16beavergroup.org/korea.

3 Quote from an interview included in the installation by Sangdon Kim, Little Chicago.

4 See Seungsook Moon, Militarized Modernity and Gendered Citizenship in South Korea (Durham: 2005, Duke University Press).

5 For examples, see The Battle of Visions, exhibition catalogue, October 11-December 3, 2005, Kunsthalle Darmstadt.

6 Chalmers Johnson, Nemesis: The Last Days of the American Republic (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006).

7 Mark L. Gillem, America Town: Building the Outposts of Empire (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), pp. xiii-xiv.

8 See Michael T. Klare, Rising Powers, Shrinking Planet: The New Geopolitics of Energy (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006).

9 Charles Armstrong, “Contesting the Peninsula,” in New Left Review 51 (May-June 2008), p. 154.

10 Among recent events, the closure of the American airbase in Manta, Ecuador, and the tremendous resistance against the new facilities in Vicenza, Italy, are worth one’s attention. See http://www.no-bases.org and http://www.nodalmolin.it. For the latest on the planned American megabase in Pyeongtaek, see http://saveptfarmers.org.

A Walk to Remember, A Walk to Invision

http://www.newmuseum.org/exhibitions/398

5/8/08 - 7/6/08

Museum as Hub space, 5th floor

Dongducheon: A Walk to Remember, A Walk to Envision

Guest curator Heejin Kim, Insa Art Space, Seoul, Korea

The complex and contradictory national characteristics of modern Korea are condensed in the region of Dongducheon, the subject of Insa Art Space’s Museum as Hub presentation on the topic of neighborhood. With a population of 88,000 people, Dongducheon is a small city located between Seoul and the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Because of its geographical conditions, surrounded by a wall of mountains and a stream running right through the middle of the city, Dongducheon has been a crucial military base of the Japanese imperial army and then the US armed forces stationed in Korea over the last century. Dongducheon has evolved through a long historical process and its history is full of conflicts and regrets, prosperity and downfall, despair and hope. What is crucial in these histories is the motivation and awareness of the issues by local residents who believe in the significance of these memories, histories, and narratives as something worthy of representation and documentation.

Insa Art Space has commissioned Sangdon Kim, Koh Seung Wook, Rho Jae Oon, and siren eun young jung to work on projects about Dongducheon and to participate as members of a collective team, along with project commentators, designers, local activists, and IAS to realize this project. For the team, the Dongducheon project is an act of rousing consciousness in individuals as subjects and social beings through encounters, dialogue, and participatory activities. Theirs is an active process of intervention, documentation, and evolution that is open to various methods and strategies.

A partnership of five international arts organizations, Museum as Hub is a new model for curatorial practice and institutional collaboration established to enhance our understanding of contemporary art. Both a network of relationships and an actual physical site located in the New Museum Education Center, Museum as Hub is conceived as a flexible, social space designed to engage audiences through multimedia workstations, exhibition areas, screenings, symposia, and events. Initiated by the New Museum in 2006, the partnership includes Insa Art Space (Seoul, South Korea); Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo (Mexico City, Mexico); Townhouse Gallery of Contemporary Art (Cairo, Egypt); and Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, The Netherlands).

Images TOP

+

Sangdon Kim, Foreign Apartment, 2008

Still from two-channel video with sound, 9:31 min

Courtesy the artist

+

Sangdon Kim, Hold your breath for four minutes—The Cemetery, 2008

Still from single-channel video with sound, 4 min

Courtesy the artist

+

Rho Jae Oon, Bite The Bullet!, 2008

Detail from Web project, *.exe, bite-the-bulletz.net

Courtesy the artist

+

Koh Seung Wook, Driveling Mouth, 2008

Still from single-channel video with sound, 13:40; tent, 4 7/8 x 4 7/8 x 6 1/2 ft / 1.5 x 1.5 x 2 m

Courtesy the artist

+

Sangdon Kim, i've seen that road before, 2008

Detail from artist’s book, 48 pages, edition of 500, 5 1/2 x 8 1/4 x 1/4 in / 14 x 21 x 0.5 cm

Courtesy the artist

+

Sangdon Kim, Little Chicago, 2008

Detail from ink on photographs, dimensions variable; wood pole with plastic branches and carpet, 200 x 60 cm

Courtesy the artist

+

siren eun young jung, The Narrow Sorrow, 2008

Still from single-channel video with sound, 14:11 min

Courtesy the artist

Profiles TOP

siren eun young jung

Born 1974, Incheon/Lives and works in Seoul

jung’s photographs, videos, and installations recall people who exist among us, yet are invisible. The “invisible” are unregistered, undocumented, and unidentified individuals marginalized from the common vernacular language, and instead, have their own nonverbal counter-languages. jung’s consistent endeavor is to identify and enrich the vocabularies of these counter-languages in art by questioning the ethics of representation and the politics of such collective sentiments as loss, agony, remorse, and sadness.

Sangdon Kim

Born 1973 in Seoul/Lives and works in Seoul

Sangdon Kim’s work addresses socio-political and ecological issues through research-based, collaborative community projects in such contested sites as Seoul, Pyeong-taek, Yeojoo, Busan, and most recently Dongducheon. His projects address the effect of government policies and economic globalization on minoritized citizens and the creative potential of a society. Operating at the intersection of art and cultural activism, Kim creates a meeting ground where local communities, activists, and artists can engage in productive dialogue and provocative understanding of the area of focus.

Rho Jae Oon

Born 1971, in Daegu/Lives and works in Seoul

Rho Jae Oon produces meta-narrative with drifting images and sound archived from the Web. His work starts with meticulous research and the archiving of image clips and sound files, which he appropriates and recomposes into his own narrative. His narratives never directly describe a specific context, but allude to a context’s socio-political issues. His final Web “publications” take the form of loose random sequences divided in chapters, often recalling sci-fi novels, and can be compared to contemporary literature, music, and painting.

Koh Seung Wook

Born 1968, Jeju Island/Lives and works in Seoul

Koh Seung Wook uses photographs, installation, and video for his conceptual projects criticizing art systems and conventional art practices. In his solo show “Please Honor Me with Your Attendance,” Koh presented a text piece appropriating the gallery’s rental contract. Since then, he has presented performance-based photo and video works such as Playing in a Vacant Lot and Triathlon, criticizing progress-driven urbanization and industrialization. Koh currently works as a director of alternative space pool, for which he is organizing a seminar series on autonomous civilian movements based on regional understanding and solidarity in East Asia.

Sponsors TOP

Insa Art Space’s presentation for Museum as Hub is made possible, in part, by a grant from the Asian Cultural Council.

Museum as Hub is made possible by the Third Millennium Foundation.

With additional generous support from ![]() .

.

Additional support is provided by the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, and the New York State Council on the Arts.

Endowment support is provided by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the Skadden, Arps Education Programs Fund, and the William Randolph Hearst Endowed Fund for Education Programs at the New Museum.

기억을 위한 보행, 상상을 위한 보행

2008. 7. 16 – 8. 24 인사미술공간, 서울

동 두천은 면적 96㎢에 인구 8만 8천명을 가진 작은 도시이다. 서울과 휴전선의 중간 지점에 위치한 이 도시는 일제 식민시절부터 반 세기를 넘게 외국 군사 주둔지로 할당되었다. 동두천 면적의 거의 절반이 현재 미군 주둔지이며, 나머지 대부분은 산으로 둘러 쌓여있다. 이러한 틈바구니 속에서 동두천 사람들은 거대한 구조적 힘이 만들어낸 일방적인 정책에 굴복하는 것 말고는 자신들의 생존을 위해 선택할 것이 없었다. 더욱이 이 도시는 오로지 군대 주둔지로만 충족되었고, 구조화되었으며, 기술되었다. 여기서 문제는 외부의 보이지 않는 손이 배후에서 동두천에 가해온 지속적인 간섭, 규제, 통제의 수위와 방식이 너무나 근본적이고 지속적이었기 때문에 어느덧 지역 공동체간의 인식, 소통, 관계의 차원까지 침투했다는 것이다. 이제 새로운 세계 질서와 나날이 팽창해가는 글로벌 자본주의, 기업 개발주의, 경쟁적인 민영화의 시대 속에서, 이 도시는 집단적 부정, 조작, 소외, 망각과 비가시성의 장소로서 우리 눈 앞에 헐벗은 채 서있다.

동두천 프로젝트는 이 프로젝트에 참여한 창조적인 공적 행위자로서 작가와 그들의 미술작업에 힘입어 지역에 대한 재해석, 표현, 발언, 소통, 행위의 매개체가 되길 제안한다. 이 노력은 그간 동두천에 대한 외면과 오해에 무의식적으로 동조해 온 우리 스스로의 마음가짐과 태도를 비판적으로 재인식하게 할 것이다. 오늘의 예술 생산과 문화 담론 구조 속에서 동두천을 발견하는 첫 번째 시도인 이 프로젝트는 동두천과 유사한 "이웃" 지역에 대한 다양한 인식과 논의를 일깨움으로써 자발적인 지역 목소리를 뒷받침하는 동시에, 동두천의 미래를 논의하는 장을 조성할 수 있으리라 믿는다.

동두천 프로젝트는 장기간의 지역 근간 프로젝트로서, 작가들의 지역 공동체에 대한 경험과 지식이 심화되어 감에 따라 작업 주제와 형태, 방법론을 지속적으로 발전시키고 조율해왔다. 이 프로젝트는 동두천을 맥락화하는 수 많은 사회적 기제들 중에서 무엇보다 우선권을 지역 공동체 주체들에 두고자 한다. 작가들은 개별적 작가적 특성에 맞추어 각각 상이한 지역 공동체에 다가가고 그들의 가장 절박한 사항을 다루는데 적절한 다양한 표현방식과 아이디어를 전개한다. 이 과정에서 먹고 걸으면서 생겨나는 일상적인 대화들, 비공식/공식 인터뷰, 기록/문학 자료 조사, 현장 답사, 자발적 참여로 이루어진 교육적 워크숍을 포함하는 다양한 소통의 형태가 모색되었으며, 이것은 최종 작업에 다양한 방식으로 활용되었다.

이미지 아카이브와 문학 텍스트로 구성된 고승욱의 싱글 채널 비디오 ’침을 부르는 노래’에서 그는 무명 상태로 남아있거나 혹은 잘못 명명되어진 주체들을 올바르게 역사 속에 "호명"하는 이슈를 제기한다. 어떤 주체들이 무명, 미명 혹은 오명 되어있다는 것은 오늘날 그들에 대한 토론과 이해를 오도하고, 그들에 대한 일체의 "표현" 자체에 어려움을 주기 때문이다. 주로 현장에서의 주민 인터뷰와 대화에 기초해 작업하는 김상돈은 신작 ’리틀 시카고’와 ’외인 아파트’, ’4분간 숨을 참아라’에서 지역 주체들이 외부의 리얼리티와 조우하는 지점을 주목한다. 주민들이 외부의 현실과 맞닥뜨리는 지점에서 주민들은 그들만의 언어를 고안해내고 기억을 선택, 개조해 가는 방식을 통해 현실을 직면하고 대응해 가는 생존 태도를 보여주고 있다. 정은영은 'The Narrow Sorrow'를 통해, 현재 동두천에 거주하고 있는 클럽여성들의 '거주지'의 형태에 집중한다. 작가는 그녀들의 일상적이며 동시에 사회적인 '장소'를 표시하고 그녀들의 들리지 않는 '소리'들을 드러내어, 소외된, 미등록의, 미확인된 존재들과의 슬픔을 나누는 제식을 제안하며, 이 슬픔은 여자들의 집으로 통하는 '좁은narrow'문의 풍경으로 모여든다." 마지막으로 노재운의 작업 ‘총알을 물어라!’는 미디어 속에 나타나는 과거와 미래의 시뮬라크럼을 통해 근본적인 차원에서 구조화되고 있는 지각과 인식의 문제를 제기한다. 그는 클래식 전쟁 영화에 나타난 은유적인 핵심 이미지에 대해 고찰하고, 이들이 글로벌 유통망을 통해 유포되면서 결국에는 우리의 미래마저 그렇게 상상하도록 프로그래밍하는 양상을 드러낸다.

이 전시에 맞추어 고승욱, 김상돈 두 작가가 제작한 아티스트 북이 출간된다. 인미공은 작가와 작품이해 외에 토크와 강연 프로그램, 해외 필진들의 글을 보탠 동두천 프로젝트 도큐먼트집을 발간할 예정이다.

캠프님블과 포크레인

2007 년 1월 17일은 동두천내의 미군부대 중 첫 반환지(말이 좋아 반환이지 실은 공시지가로 환산한 땅값을 그대로 받아 되파는 것. 공으로 먹은 땅을 팔아서 이전비용 까지 다 받아먹겟다는 희안한 계산법이다)인 캠프 님블이 처음으로 일반에게 공개되었다. 국방부와 환경관리공단이 측정한 오염도 조사결과를 발표하고 현지를 답사하는 형식으로 이루어진 이날의 행사에서, 동두천 시민연대 강홍구 대표가 추상적인 발표내용에 이의를 제기하고 다소 호전적인 제스쳐를 보이며 포크레인으로 땅을 직접 파헤쳐 볼 것을 강력히 제안했다.

예 상치 못했던 문제제기에 당황한 국방부와 환경관리공단 관계자들은 포크레인의 진입에 대해 극구 반대했으나 결국 캠프 님블의 정문을 통해 포크레인이 밀고 들어오게 되었고 환경관리공단측이 전혀 문제되지 않는다고 발표한 두지점을 실제로 파 내어 그 중 한 곳에서 엄청난 휘발류 냄새가 풍기는 심한 오염상태를 확인하였다. 시민연대의 회원들이 이 흙을 일부 채취하였고, 이 흙의 반출을 막는 국방부와 환경관리공단 관계자들과의 심각한 몸싸움이 오갔고, 결국은 흙보따리를 가지고 나올 수 있었다.

20090802

그/녀는 누구인가?

…지하에 대해서라면 한남연립 마동 베란다에서 욕망할 문제가 아니다. 나는 당신의 지하를 구경할 수 있는 베란다를 욕망한 때가 있었다. 거기서도 널어놓은 팬티는 잘 마르는가? (김행숙, 지하 1F에 대해서 중.)

지하에 대해서라면 잘 마르지 않은 팬티를 입고 완벽한 S라인을 유지하고 있는 저 핑크색의 몸들이 욕망할 곳은 아닐지 모르겠으나, 다만, 이들의 지하세계를 구경하기를 욕망하는 사람들의 행렬이 끊이지 않고 있다 하니, 가끔은 팬티가 바짝 마르는 볕 좋은 로얄층의 베란다보다 지층의 축축한 습기가 나을 때도 있긴 한가보다. 어쨌거나 들려오는 이야기에 따르면, 이 핑크색의 몸들은 지하 1층에 살고, 팬티를 입기는 한다고 한다. 간혹 팬티를 벗는 날이 있다고도 하는데, 팬티가 축축해서 인지 어쩐지 그 이유는 알려진 바가 없다.

이웃의 남자는 이 지하 일층을 한참 동안이나 욕망하고 또 욕망하였다. 그가 욕망한 것이 지하 일층이었는지, 핑크색이었는지, 비키니였는지, Virgin이었는지, S라인이었는지, 혹은 하이힐, Sexy, 아니면 Event거나 Bar였는지 정확히 알 수는 없었지만 남자의 욕망은 커져만 갔다. 몇 날 며칠을 고통스런 얼굴로 벼르고 벼른 끝에 결국 그곳에 비밀스레 다녀온 그의 얼굴은 다소 거만한 미소로 가득 차 있었다고 기억한다. 그리고 그는, “비키니를 입은 여자들이…”로 입을 열어 자신이 본 것들에 대해 자랑스럽게 설명하기 시작했다.

‘여자’에 대해서라면 핑크, 비키니, Virgin, S라인, 하이힐, Sexy, Event, Bar, 그리고 지하 1층으로 설명될 수 있는 문제는 아니다. 사실을 말하자면, 나의 지인들 가운데 요통을 무릎쓰고 척추에 힘을 주어 그다지도 요염한 몸짓을 만들어 낼 수 있는, 혹은 내고자 하는 존재라면, 끼 떨기라면 누구에게도 뒤지지 않을 게이인 S 씨와 우아함과 화려함의 정수를 보여주는 트렌스젠더 B씨 이외에는 참으로 보기 힘든 경우라는 것이다. 어째서 이웃집 남자는 저 간판의 핑크색 몸들이 당연히 ‘여성’이었다는 사실을, 저 간판이 지시하는 것이 여성의 몸을 교환경제의 상품으로 삼고 있다는 것임을, 여자인 나보다 먼저 알아챈 것일까? 어째서 이성애자 남성의 욕망은 이다지도 쉽사리 그 응답을 들을 수 있는 것일까?

일찍이 “여성은 남성들간의 교환대상”이라고 성토한 게일 루빈Gayle Rubin의 말을 떠올렸더라면, 이웃집 남자를 비롯한 수많은 남자들의 눈 밑을 나날이 검게 만든 이 핑크색의 몸들이 ‘여성’이라는 젠더로 호명되어 남성들 사이에서 교환된다는 사실을 진작에 눈치챘어야 했을 것이다. 아무런 개연성이 없는 기표들로 가득한 이 기이한 간판이 실은 ‘여성’이라는 기호를 구성하고 있다는 사실을 찰떡같이 알아 들었어야 했다는 말이다. “‘여성’은 기호이며 재현”이라고 말했던 저명하신 페미니스트 이론가 테레사 드 로레티스Teresa De Lauretis의 전언마저 떠올렸더라면, 이 간판이 보여주는 본질론적인 재현의 전략과 억압의 구조에 몹시 분노함으로써 이 재현을 재배치 할 수 있는 능력을 가진 나의 페미니스트로서의 정치적 올바름을 재확인해 마땅한 순간을 누렸어야 했을지도 모를 일이다. 그러나 나는 다시금 이 간판 앞에서 고개를 갸우뚱한다. ‘여성’이라는 기표가 특정한 ‘몸’을 투명하게 명시한 적이 있던가? 저 핑크색의 몸 어디에 여성과 여성성이 재현되고 있단 말인가? 이 과도하기 짝이 없는 포즈가 즉 여성성임을 인정한다면, 나의 죄 없는 친구들인 S씨와 B씨가 전시하는 여성적인 몸은 또한 어떻게 재현될 수 있단 말인가? 게다가 이 여성적인 몸을 욕망하는 퀴어Queer들의 욕망은 저 지하의 공간 안으로 밀려 들어갈 수 있을 것인가? 난대 없이 젠더간의 경계를 흩뜨리고 젠더퀴어들을 불러모으는 핑크색의 그/녀는 (대체) 누구란 말인가?

…당신은 어디에 있는가? 나는 갈 데까지 갔어도 당신의 지하를 구경할 수 있는 베란다는 욕망의 영역이다./ 나는 저녁에 화분을 사러 나갈 것이다. 나는 베란다의 여자답게 꽂힐 것이다. 물주러 오는 남자는 병신이다. (김행숙, 지하 1F에 대해서 중)

<교통정보>

‘예술적 실천’으로서의 투잡족을 변명하며@Beyond Art Festival Anthology Magazine 제 1호

@Beyond Art Festival Anthology Magazine

나의 십대는 언제나 지루하고 피곤했다. 가혹하기 짝이 없는 엄마의 기상 명령과 함께 시작되는 하루는 매일매일이 똑같았다. 자고 일어나 학교에 가고, 학교에 가면 다시 잠을 잤다. 학교에서 돌아오면 미술학원에 가서 그림을 그리고, 미술학원에서 돌아오면 독서실에 가서 잠을 잤다. 그리고 독서실에서 돌아오면 방에 앉아서 벽지의 무늬나 얼룩 같은 것을 쳐다보며 멍하니 앉아있곤 했다. 하루 세끼를 빠짐없이 먹었고, 하루에 한번씩 꼭 똥을 눴다. 하기 싫은 일을 해야 할 땐 몇번이고 똥이 마려웠다. 생각하기 싫으면 잠을 잤고, 생각하고 싶을 땐 책을 보거나 비디오를 빌려다 봤다. 연예인을 따라다니며 수선 떠는 건 유치해 보였고, 찌질한 남자애들을 사귀는 건 영 땡기지가 않았다. 가출을 하는 건 무서웠고, 손목을 긋는 건 아플 것 같았다. 겁이 많고 말 수가 적은 소심하고 평범한 아이였던 나는 이 지겨운 나날을 언제까지 살아야 하는지가 궁금할 뿐이었다.

가수면 상태의 삶이 수년간 지속되는 와중에도 그나마 책상 밑에 만화책을 사 모으거나, 미술학원이나 독서실에 가는 척 하고는 성인 영화를 상영하는 극장 앞에 줄을 서거나, 좀 ‘노는’ 애들과 어울려 지하카페의 어둑한 곳에 자리잡고 앉아 매캐한 말보로의 연기 속에 끼어들어가는 정도의 소심한 ‘딴짓거리’를 하며 가늘게 숨통을 틔웠다. 생각해보면 그리 짜릿한 일도 아니었는데, 문장의 5형식이나 근의 공식을 외우는 일, 혹은 아그리파의 얼굴을 쏘아보거나 광나게 아름다운 사과를 그려대는 일 보다는 조금 나았던 것일까. 예고 실기 시험을 앞둔 바로 전날엔, 어쩐지 마음이 삐딱해져서는 저녁밥상머리에서 언니의 얼굴을 향해 젓가락을 냅다 집어 던지고는 아버지에게 ‘반 죽도록’ 맞았다. 아마도 이 일이 내 지루한 십대를 관통하는 가장 지루하지 않은 사건이라면 사건이었을까. 어쨌거나 대체로 아무 일도 일어나지 않은 나의 십대는 어느 날 그저 그렇게 사라져 버렸다.

누군가의 삶이 지루하건, 누군가의 삶이 고통스럽건, 또한 누군가의 삶이 즐거워 미칠 지경이건, 세월은 곤조있게 흐르고, 나의 십대는 사라진 지 오래고, 예고시험은 보기 좋게 떨어졌지만 무사히 미술대학을 나왔고, 대학원까지 나왔고, 그렇게 20대가 사라지고, 심지어 유학까지 다녀오고, 삼십대인 지금 십대인 아이들을 만나고 있는 중이다. 어쩌다 일이 이지경이 되었는지는 모르지만 십대들과 함께 보내는 내 삼십대는 지루함을 느끼기는커녕, 똥이 마려울 새도 없이 숨가쁘게 돌아가고 있는 중이다. 내가 일하고 있는 곳은 <하자센터>라는 이름으로 불리우지만, 공식적인 명칭은 <서울시립 청소년 직업체험 센터 (http://www.haja.net)>이다. 제도학교에 적응을 못하거나 쫓겨난 불량 청소년들이 다니는 대안학교이거나, ‘튀는’ 아티스트들을 길러내는 귀족 예술학교정도로 이해하고 있었던 많은 사람들이 <하자센터>의 공식명칭을 이야기 해 주면 무척 놀라곤 한다. 무언가 비범한 아이들의 집합소에서 창의력이 펑펑 치솟는 일을 하면서 제법 명예롭고 흐뭇한 꼰대질을 하고 있다고 생각하는 건 정말이지 오해다.

하자센터에는 정말로 다양한 아이들이 한 해에도 수 천명씩 드나든다. 하자센터를 구성하는 몇몇 파트 중 가장 큰 부분의 하나인 ‘하자작업장학교’에는 매해 5-60명의 아이들이 이곳을 자신의 학습공간으로 삼고 상주한다. 또 다른 작은 학교인 ‘글로벌 학교’에는 약 10여명, ‘일과 요리팀’에 약 10여명, 공연팀인 ‘노리단’에 30여명 가량의 십대들이 상주하며, 강좌형 프로젝트에 참가하는 아이들이 약 500여명, ‘일일직업체험’에 참가하는 아이들이 약 천여명, 그 밖에도 수시로 생겨나는 크고 작은 기획형 프로젝트들에 참가하는 아이들 수백명이 들낙거린다. 센터 내에서 상주하는 아이들은 대개는 어떤 이유로건 탈 학교를 경험했거나 아예 제도권 교육 자체를 경험하지 않은 아이들이다. 단발적으로 하자센터를 찾는 아이들은 여전히 제도 학교를 다니고 있거나, 홈 스쿨링을 하거나, 다른 대안학교를 다니기도 한다. 드나드는 아이들의 숫자와 다양함 만으로도 하자센터는 다이나믹하기 이를 데 없지만, 프로젝트들이 만들어지고 진행되는 방식과 그 스피드의 다이나믹함은 말할 것도 없고, 이 수많은 아이들이 빚어내는 ‘사건, 사고’들을 따지고 들자면 생각만으로도 호흡곤란이 올 지경이다.

‘예술가/작가’로서 자신을 정체화 하고자 하는 내가 미술판 보다는 청소년 기관에서 머무르는 절대적인 시간이 더 많다는 것은, 고백하건데, 매 순간 자신의 존재감을 의심하고 우선순위를 따지느라 죽상을 때리고 있다는 뜻이다. 게다가 작업 이외의 일에 ‘먹고 사는’ 문제 이상의 윤리적 개념들이 개입하기 시작하면 이제 지난하고 지난한 선택의 릴레이와 분열된 감정들간의 경합이 벌어지기 시작한다. 주변의 사람들은 의례히 묻는다. 무슨 예술가가 출퇴근을 하며 목을 죄는 회사원생활을 하느냐, 혹은 거기서 무슨 과목을 가르치냐, 거기 애들은 엄청 예술적이냐, 모 이런 식으로. 대답하기가 늘 난감하지만 열심히 대답을 하려고는 한다. 왜냐하면 그러한 질문들에 성의껏 대답하는 일은 또한 나 스스로를 납득시켜 나가는 과정이기도 하기 때문이다.

직장에 매어있다는 것은 상상한 것 보다 훨씬 더 갑갑한 것이었지만, 그렇다고 정기적인 출퇴근이 예술가의 삶과 만날 수 없는 지점에 있다고 생각하지는 않는다. 내가 미술활동을 삶의 한 실천으로서 선택한 것이라면 아이들과 함께 ‘일’하는 것 또한 예술적 실천의 또 다른 모습일 수 있다. 이 삶의 활동에는 물론 ‘경제활동’또한 포함된다. 자본이 모든 것을 규율하고 있는 이 시대에 조차 가난한 예술가라는 미덕과 예술가는 돈을 만져서는 안 된다는 이상한 신화들이 여전히 우리를 지배하고 있다는 것을 알지만, 나는 예술가들이야말로 경제활동과 같은 가장 일상적인 삶을 실천 해야 한다고 믿는다. 물론 언제나 작업을 할 절대적인 시간의 빈곤과 부자유에 울상을 짓게 되지만 말이다. 어쨌거나 나처럼 자신의 ‘예술활동’이 시장경제의 가치로 잘 환산되지 않는 사회적/개념적 프로젝트형 작업을 진행하는 많은 작가들의 ‘경제활동’은 종종 ‘예술활동’과 한참씩 멀어져 버리기도 하지만, 달리 생각하면 소위 임노동이라 할만한 모든 일들이 오히려 예술적 활동의 근저에 자리할 수도 있다는 것이다. 물론, 하자센터는 다른 직장들과는 달리, 직원들의 외부활동을 존중해주고 지지해 주는 편이기 때문에 이러한 생각이 가능할 수도 있을 것이다.

무슨 과목을 가르치냐라는 질문 역시 참 대답하기 괴롭다. 이러한 질문은 사실 미술대학으로 대표되는 미술계의 메이저리그에서 훈련된 미술 인력들이, 전통적 의미의 분과학문적 틀을 벗어나지 못한 채 쉽게 물을 수 있는 질문이다. 장르와 경계를 끊임없이 해체하면서 가장 포스트 모던하고 진보적인 관점을 부단히 만들어왔던 예술가들이 오히려 더 쉽게 이런 질문을 하는 이유는, 여전히 미술인력을 생산하는 시스템이 미술대학 이외에는 거의 존재하지 않다는 사실을 잘 알고 있기 때문이다. 나는 그래서 하자센터라는 아카데미아 권위 밖의 공간을 통해 작업자로 성장하고자 하는 아이들을 만나는 것이 녹록한 일이 아니라는 것을 잘 알고 있다. 일 종의 부채감이나 책임감마저 작동시키게 하는 이 기묘한 상황에도 불구하고 이곳에서 아이들과 만나고 있는 것은 아이들에게 작업의 스킬을 가르치기 위해서가 아니라 아이들과 어떤 성장의 길을 함께 모색할 수 있는지를 부단히 실험해야 하기 때문이고, 삶을 살아가기 위한 내면의 힘을 다지기 위해서이다. 말하자면, 내가 하자센터에서 하는 일은, 무엇이 ‘되기 위해’ 해야 하는 것들을 아이들에게 학습시킨다기 보다는, 무엇이 되어서든 멋지게 살아갈 수 있는 ‘태도’와 ‘힘’을 나누는 일이다. 그리고 그 과정을 통해 나 스스로의 삶 또한 끊임없이 성찰해 내게 된다.

거기 애들은 좀 남다르지 않냐는 물음에 대답하는 것이 실은 제일 곤혹스럽다. 남다름이란 종종 비범하기 이를 데 없는 특별한 재능 같은 것을 이르기도 하지만, 가끔은 일반적인 잣대를 들이대며 언급 했을 때는, ‘정상적인 길’에서 완전히 빗겨나 삐딱선을 타버린 ‘불량한’ 애들로 이해되어버리기 쉽기 때문이다. 사실 십대라는 존재들을, 더구나 천명이 넘는 아이들을 어떠한 말로건 보편화 시킬 수 있다는 믿음은 오만이거나, 혹은 폭력이다. ‘아이들’이라는 존재는 귀신, 여자, 이주민, 혹은 동물만큼이나 주변화되어 보이지 않는 존재들이다. 적당히 규율 되어 제도 내에 포섭되어야 하는 이 ‘타자들’이 제도의 권위를 위반하고 그것을 공격할 때 두려움에 떠는 것은, 실상 어른들이고 그들이 굳건히 지키고자 하는 단단한 세계의 질서이지, 아이들 자신은 아니다. 이 아이들이 일상에서의 저항과 위반을 빈번히 일삼는 만큼이나, 저항이며 위반인 어떤 ‘언어’를 가지게 된다면 얼마나 짜릿할 것인가 하는 상상이 나를 하자센터로 이끌었다. ‘남다르다’는 것이 무엇인지를 자신들의 언어로 말할 수 있게 되도록 이들의 조력자가 되는 것이 나의 일이라는 생각도 했다. 그렇지만 역시 ‘어른’인 나는 아이들 언어와의 소통 속에서 빈번한 오해와 오독을 경험하며 헉헉대는 중이다. 언젠가 그들의 저항언어로 나를 초대 해 줄 날을 손꼽아 기다리며.

십대를 ‘잠’속에 실어 보낸 것은 그저 나의 불운이었지 라며 자조 섞인 한탄을 하고 있는 것 만으론 어쩐지 찜찜하다고 생각하던 때, 나는 우연찮게 십대들을 만나고 있는 삼십대를 살고 있었다. 시대는 바야흐로 완벽히 균질화된 ‘일반적’질서로 아이들을 불러들이고 있지만, 그럴수록 아이들은 지쳐 나가 떨어지기 보다는 세상을 조롱하면서 자라난다. 가장 엉뚱한 곳에 자리를 잡고, 비루한 상상력을 지껄이며, 바닥에서 꿈지럭거린다. 의도적으로 어른들의 말을 못들은 체 하며, 토굴을 파고 기어들어가거나 저열하기 짝이 없는 외계어로 웅얼거리고, 끝없는 잠에서 깨어나지 않거나, 어른들의 기대를 무참히 짓밟아 준다. 어른들은 혀를 차며 이 아이들을 꾸짖지만, 아이들에게 이토록 참을 수 없는 시대를 물려준 이들은 대체 누구란 말인가. 적어도 나의 미술활동이 세계의 질서를 교란하면서 그에 대항하는 저항언어를 만들어 내는 것이라 스스로 정의한다면, 나는 마땅히 이 아이들과 만나고 있어야 하는 것이다.

앞서 줄줄이 써 내려온 대답들을 다시 나에게로 돌려주면서, 나는 참 다행이다라고 생각한다. 어깨를 내리누르는 무거운 일거리들을 떠올리며 이내 한숨을 푹 내쉬고 말 것이 뻔하지만 말이다. 그러나 언제건 삶이라는 것이 그리 호락호락한 적이 있었던가, 혹은 누구의 삶이 더 쉽거나 어렵다고 말 할 수 있을 텐가 라고 묻는다면 그저 입을 다물고 해야 할 일들을 하나씩 해나갈 뿐이다. ‘예술가의 존재감’ 따위를 반복해 물으며 죽상을 쓰는 대신, 투잡족의 지치지 않을 강인한 체력을 위해, 인삼 깍두기를 담가 먹건, 발바닥에 불이 나게 파워 워킹을 연습하건, 몸짱 아줌마의 비디오를 구입하건 간에 무엇이든 묘안을 찾아보는 것이 더 즐거울 수 있다는 것은 십대든 삼십대든 바보가 아니라면 다 아는 이야기일 테니 말이다.

무반댁

푸딘댕-위앙짠-방콕-무반댁(깐짜나부리)

어 제의 이별파티에도 불구하고, 아침부터 동네아이들이 농장으로 하나둘 모여들기 시작했다. 우리가 떠나는것을 배웅하기 위해서였다. 더군다나 오늘 따라 학교 선생님들의 회의가 있다고 해서 오후 수업만 한다고 하니, 오전에 학교에 가지 않아도 되는 아이들이 찾아와 군데 군데 모여서서 아이들을 기다린다. 우리 아이들은 짐을 싸다 말고, 자신들을 배웅하기 위해 와준 친구들에게 인사를 하느라 정신이 없다. 우리를 공항까지 실어갈 벤이 이미 도착해서 기다리고 있는데도 아이들은 눈물을 하염없이 쏟아내며 이별인사를 한다.

아 이들을 진정시키고, 짐을 챙기게하고, 차에 올라타게 하는데에만도 몇십분이 흘렀다. 차에 올라타서도 눈이 벌게지도록 울어대느라 그렇게 한시도 쉬지않고 시끄럽게 떠들어 대던 아이들의 입이 닫혀버렸다. 우리는 무반댁에서 다시 새롭게 만나야 할 아이들이 있으니 그 슬픈 감정은 조금 미루어 두는 것이 어떻겠느냐고 아이들에게 조언한다. 차안에서 조용히 음악이 흘러나오고, 창문밖으로 흘러가는 푸딩댕, 라오스의 풍경들이 눈동자를 떠나간다. 흙먼지가 날리고, 여전히 비닐봉지가 흩날리는 도로변의 풍경은 이곳에 도착한 첫날에 본 풍경과 똑같은 것임에도 전혀 다르게 느껴졌다. 이 풍경들을 놓칠새라 나는 눈을 깜빡이는 것조차 아까운 마음이 되어버렸다.

네 시간 가량을 지나 위앙짠 공항에 도착했다. 이제 방콕으로 가는 비행기를 타고 방콕에서 무반덱까지의 여정이 남아있다. 작은 라오스 공항을 통과해 작은 경비행기에 올라타 작고 귀여운 기내식을 받아들고 이 작은 나라에 대해 생각한다. 아무것도 가진것이 없는 땅. 기차가 없고 학교가 없고 병원이 없고 돈이 없는 땅. 그러나 아름다운 자연이 있고, 아름다운 사람과 마음이 있는 땅. 제국주의자나 인종주의자가 될 수도 없지만, 낭만주의자는 더더욱 될 수 없는 이 땅위에서, 나는 적어도 작은 감동과 기쁨을 분명히 확인하고 왔음을.

ps. 방콕 공항 도착. 무반댁으로 이동. 이동중 맛있었던 태국식 저녁식사