50 Ways to Leave Your Lover

July 15, 2008Exit Strategies from Liberal Empire

Sangdon KIM, Discoplan

Along the river bank in the city of Dongducheon, some twenty miles north of Seoul in the Republic of Korea, the artist Sangdon Kim organized a hilarious public performance. Participants were invited to create slingshots, kites, catapults, flying machines – in short, to hurl every imaginable homemade projectile over the rusty razor wire separating them from the recently vacated U.S. base of Camp Nimble. The missiles carried a payload of clover seeds, which in the best of cases could scatter on impact, sprout, flourish, cover the ground and begin remediating the poisoned soil left behind by decades of military occupation. The kids got ready, took aim, failed miserably for the most part, and burst out laughing with each fresh attempt. The adults enjoyed some pointed comments about the hidden costs of the U.S. force relocation plan, and speculated about possible consequences for their city. The video of the event shows moments of collective reflection and heartfelt comic relief – the feeling that you’ve finally got free of something.1

I am an American, and like most, I’m ignorant of what’s done in the name of democracy by the U.S. military. Whether it’s the raw facts of land occupation by sprawling bases, the tangled histories of collaboration with host nations, or the latest plans for the use of these lethal installations, I have everything to learn. When I arrived I didn’t even know the name of Guem-i Yun, and couldn’t imagine that the artistic performance at Camp Nimble was also intended to commemorate the day, fifteen years ago, when this 26-year-old club girl was brutally raped and murdered by Pvt. Kenneth Markle in Dongducheon on October 28, 1992. But I did know that prostitution around American bases in Asia has been a continuous scandal since WWII, and when I was asked to give a lecture on the Dongducheon project, images of neon-drenched R&R districts and men in enormous armored vehicles swirled confusedly to mind. How to approach such an overcharged issue? The inspiration that struck was a 1975 radio hit by Paul Simon, where the singer explains – or rather, has explained to him – that there must be 50 ways to leave your lover. Though it’s all about an ending, you realize something new is also in the works:

You just slip out the back, Jack

Make a new plan, Stan

You don’t need to be coy, Roy

Just get yourself free.

Hop on the bus, Gus

You don’t need to discuss much

Just drop off the key, Lee

And get yourself free.

After eight long years of the Bush administration’s useless wars, I want OUT of the obscene and seemingly endless love affairs between the U.S. and its army, whether in Iraq, Afghanistan, Korea, or in our own country. But despite what the song says, there is so much to discuss, so many questions, which the works in this exhibition also raise. What’s between us, as the 16 Beaver Group asked a group of Korean artists and activists, during a trip to the new American megabase at Pyeongtaek?2What would it take to exit from a sixty-year relationship that has defined the United States no less than the Republic of Korea? Above all, what does it mean to be free in an age of liberal empire?

Little Chicago and the Silver Screen

While walking around Seoul looking at the city’s splendid museums, my guide for a day, Seul Bi Lee, suggested that we try something interesting for lunch. Pude chige, it was called: “troop soup.” I found myself looking into a boiling metal pot full of tofu, udong noodles, sliced-up frankfurter sausages and macaroni. Perhaps it is when you eat something like that, and recognize the familiar tastes among the strange ones, that you start to realize what we’ve really gotten ourselves into, through the mixing of cultures and nations.

During Sangdon Kim’s research into the oral history of Dongducheon, he learned that the troops had nicknames for the local districts, like “Queens,” “Manhattan” and “L.A.” This kind of G.I. banter is familiar, because it’s the staple of novels, stories and Hollywood movies. The older residents Kim interviewed recalled the fantastic cynicism of the early days: camptown life was all about money, whether it was the soldiers selling black-market goods from the PX, the prostitutes and club owners selling sex and whiskey, or the police selling protection. One of the residents recalls the popularity of the cinemas, along with real events that seem to match the detective flicks and gangster fictions:

Around the theater, the soldiers used to sell the “Made in USA’s.” But at that time, people would just take the stuff and run. Lots of murders! The soldiers did a lot of killing, too. It was horrible! … Prostitutes getting killed, soldiers running away… Mother fuckers! Same when the 7th division was here too. Lots of fires and lots of incidents. I mean, they called here “Little Chicago,” with so many incidents! 3

Of course, everyone must eat and money doesn’t grow on trees, but it pours out where people congregate in pursuit of their pleasures. Plus everybody loves the movies. Another thing you learn from Kim’s interviews are rumors about the conversion plans for Dongducheon’s immense American bases – Camp Casey, Camp Hovey, Camp Mobile – which, it’s said, some of the town leaders wanted to turn into giant entertainment complexes with casinos, like “a Korean version of Las Vegas.” Gambling and the latest forms of electronic spectacle would replace the outdated nightclubs. In reality, a massive sporting complex has already been built, destroying part of the Sangpae-dong public cemetery as a step toward a “Free Trade City” of the future. All this appears somehow natural, when you know that after the Second World War, those involved with the geopolitics of the region – American military brass, Washington officials and local elites – made the wager that an influx of billions of defense dollars could save Asia from communism, through epic battles and dramatic armed standoffs, but also through huge procurement contracts with host-country suppliers, untold thousands of clinging cash registers at local businesses, and all kinds of shady under-the-table deals. This is what’s hinted at in the mottoes that Sangdon Kim inscribes on photographs of commonplace environments in Dongducheon: “Don’t tell the truth though it’s cold and you’re starving,” reads one. “Don’t tell the secrets though it’s hot and you’re starving,” replies the other. Everyone is supposed to keep quiet and cover everyone else’s deal.

By documenting oral histories and giving them form and context in exhibitions, artists like Kim are helping make public the close-lipped and contradictory texture of existence that has been woven around the American military deployments in East Asia since the close of the Second World War. The casual conversation of Dongducheon reads like a chapter of transnational history, lived out at intimate scale in people’s daily lives, and reflected in the violent glamor of the silver screen.

-

visit the website of the work

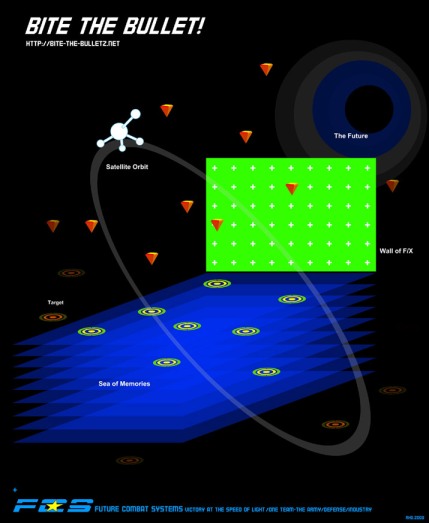

Here is an entry to Roh Jae Oon’s web-based exploration of one of the defining genres of commercial cinema: the war flick. His piece, Bite the Bullet!, is an original interpretation of the spectacle society. Dramatic images of war will be administered as an ersatz anesthetic, distracting the patient from an operation being performed on his or her own body. The 12-part work proceeds by short excerpts, sometimes from two or more films. What’s left out can sometimes be as important as what’s put in. The introductory scenes are from The Bridges at Toko-Ri, a 1954 Hollywood production about a stern admiral, a concerned wing commander, and a reluctant naval reservist flying bombing missions against North Korea. It all begins with love: a woman’s goodbye kiss to her husband departing on an aircraft carrier. What follows is a cut to a sky full of bursting anti-aircraft shells, filmed from the pilot’s perspective; then a shot of bombs destroying a bridge. The movie won an Oscar for its special effects, which are an important focus of Oon’s investigation. But another significant aspect is the famous closing line of the film, which is not included in the excerpt. Reflecting on the discipline that led his pilots to a successful mission and their own deaths, the admiral asks “Where do we get such men?” What exactly is the operation that produces them?

American combat films are about the formation of a national character in battle, a theme played out again and again in Oon’s selections. But what’s at issue in the artwork is also the influence of that process on the population of a client-state engaged in a bitter civil war, elevated to world-historical proportions by Soviet, Chinese and American rivalries. Among the South Korean films that cast their light on the complexities of this relationship is Sang-ok Shin’s 1958 classic, Jiokwha, aka A Flower in Hell, represented with an excerpt from a steamy dancing scene. What casual Western viewers won’t realize, however, is that in the film, these highly erotic sequences are interspersed with others, showing a small-time Korean gang stealing government-issue supplies from the distracted American viewers… Much of the interest and cinephilic pleasure of Bite the Bullet! lies in the ironic combinations that each viewer is free to make, between the scenes that are actually shown and those whose memory is left floating. But this free-floating memory is exactly that condition that Rho Jae Oon sought to encompass in a larger frame. The poster for the piece shows an ellipsoid satellite orbit, a screenlike “wall of F/X” (or special effects) raised bright in the sky, and a deep blue “Sea of Memories” floating down below, on which bull’s-eyes have been meticulously placed, each at its specific level. The implication seems to be that in the networked system of contemporary media distribution, each spectacular bullet can be self-targeted at the memories of individuals, administering what might be called an “anesthetic of one.”

In the last group of excerpts, propaganda images of the US Army’s “Future Combat Systems” confirm the implicit reference to the military-entertainment complex. On a text panel, network-centric warfare guru Art Cebrowski proclaims: “Either you create your future or you become the victim of the future someone creates for you.” Stated by the former director of Donald Rumsfeld’s Office of Force Transformation, which initiated the entire relocation concept that is shifting South Korea’s military geography, that becomes an intensely ironic expression of the high ambition and deep anxiety that the Dongducheon project is trying to communicate to its viewers.

From Militarized Modernity to Liberal Empire

The exhibition looks back at the past without nostalgia or resentment, in order to grasp the complexities of the present and in that way, share at least some hope of shaping the future. Even after considering barely half the pieces, one can sense that each detail and nuance has been discussed intensively during the research process, working to create that most rare of events, a group exhibition (and not just a selection of works to fit a curatorial concept). One can wonder, then, about the absence from the show of a theme that would seem to be central to its whole proposal. I am thinking about the specifically Korean form of productive discipline that Seungsook Moon calls “militarized modernity” – and of the ways that it relates to, and differs from, more characteristically American patterns of character-formation.

Moon describes how a particularly harsh form of discipline, based in large part on practices employed by the Japanese Imperial Army, was generalized to the entire male population of South Korea by means of universal conscription. It was then extended to industrial production through the Military Service Special Cases Law of 1973, which allowed men trained either at vocational at schools or science and engineering institutes to forgo military service for paid employment at defense factories or in heavy and chemical industries. The distinctly gendered male subjectivity that was developed in the military-industrial ranks through the exaltation of masculinity and the parallel denigration of female sex-objects was then reinforced in society by positive images of the man as historical hero and family provider, in contrast to the domestic and subordinated role of women.4

Moon describes how a particularly harsh form of discipline, based in large part on practices employed by the Japanese Imperial Army, was generalized to the entire male population of South Korea by means of universal conscription. It was then extended to industrial production through the Military Service Special Cases Law of 1973, which allowed men trained either at vocational at schools or science and engineering institutes to forgo military service for paid employment at defense factories or in heavy and chemical industries. The distinctly gendered male subjectivity that was developed in the military-industrial ranks through the exaltation of masculinity and the parallel denigration of female sex-objects was then reinforced in society by positive images of the man as historical hero and family provider, in contrast to the domestic and subordinated role of women.4

It would have been important to explore how this this militarized modernity expressed itself in the triple relation between the American occupiers, their ROK allies and local procurers – in every sense of the word – and finally, the male population of the city. To be sure, such subjects were raised by the Minjung painters of the 1980s, with their satirical pop-art vocabularies.5But they are far more difficult to tackle in the living reality of video. The only place in the show where they begin to surface is in the evasive replies of local inhabitants interviewed for Sangdon Kim’s video piece, Foreign Apartment, which inquires into the past functions and current ownership of a ruined white building near Camp Casey, used for prostitution in the 1960s and 70s. Just a few shreds of conversation allow us to imagine the virile discipline of a young Korean man waxing the helicopter of the 7th Division commander who came to oversee the foreign apartment.

-

Sangdon KIM, Foreign Appartment

What remains largely invisible in the show, therefore, is the lived experience of militarized modernity and its consequences on Korean subjectivities today. Rho Jae Oon has perfectly captured the dynamics of this kind of invisibility, but on the American side only. In Bite the Bullet! he presents an audio excerpt from the 1992 courtroom drama A Few Good Men, which he superimposes over touching scenes of a blind woman selling flowers, taken from Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights. On the soundtrack, a hard-bitten Marine colonel from Guantánamo, played by Jack Nicholson, defends his decision to apply deadly punitive force to one of his soldiers, reiterating the classic arguments that every American has heard in a hundred different forms: “Son, we live in a world that has walls… and those walls have to be guarded by men with guns. I have neither the time nor the inclination to explain myself to a man who rises and sleeps under the blanket of the freedom I provide, and then questions the manner in which I provide it!” But his outburst of passion is exactly what allows the young lawyer, played by Tom Cruise, to trick the colonel into admitting his own guilt before the judge.

Here we have the fundamental contradiction that structures liberal empire. On the one hand, a continuous insistence on the imperious necessity of force, to be applied under “states of exception” in distant outposts such as Guantánamo; and on the other, an unshakable confidence in the rule of law, which can always be reestablished back home by the infallible procedures of American democracy. Rho Jae Oon’s ironic superimposition of the blind flower seller onto the courtroom dialogue offers two possible readings of the situation. From the colonel’s point of view, the blindness is obviously that of a sheltered and effeminate civilian world which cannot the face the very force of arms it lives by. But from the post-9/11 viewpoint that is ours today, the blindness lies in the naïve belief that legal instruments can restrain the immense, unbridled powers of the Pentagon.

What are the actual consequences of militarized modernity and liberal empire on our societies today? This is the question that critical artists and intellectuals should never avoid, either in Korea or in America. Take, for example, an intellectual for whom I have tremendous respect: Chalmers Johnson, an American academic, Asia expert and former Cold Warrior, who coined the concept of the “developmental state” in 1982. He had already begun to learn about the secret history of U.S. foreign policy in the library of former CIA director Allen Dulles, while working as a consultant for the National Intelligence Estimate in the late 1960s. However it was only after the fall of the Berlin Wall, when the Cold War ended and American troops did not demobilize but instead remained on their vast array of outposts throughout the world, that he began to revise his views. In 1996, he visited the Japanese island of Okinawa at the request of its governor, Masahide Ota, in order to investigate the rape of a twelve-year old Okinawan girl by two Marines and a Navy seaman. There he began work on another major concept: the “empire of bases.”

More than any other single author, Johnson has revealed the secretive, abusive and fundamentally undemocratic character of U.S. military operations overseas. His latest and best book, entitled Nemesis, warns of the possible end of American democracy, if the CIA’s covert operations, the Pentagon’s secret budgets, and above all, the President’s “executive privilege” are not brought back under civilian control.6But despite all this, Chalmers Johnson has not, to my knowledge, ever revised his positive evaluation of the “developmental state” – a social order that corresponds precisely, in the South Korean case, to the industrial dimension of what Seungsook Moon calls militarized modernity. The question is whether, in the absence of such a reevaluation, one can ever understand the ongoing transition from militarized development in a country like Korea, to the self-contradictory, crisis-ridden regime of liberal empire now extending all over the world.

Johnson has led the way towards a geopolitical understanding of American militarism, by describing the network of over 750 U.S. bases on foreign soil, inhabited by approximately half a million soldiers, support staff, private contractors and dependents, and underwritten by a partially secret budget of approximately a trillion dollars a year. Mark Gillem, an architect working critically inside the U.S. Air Force, takes a further step. His recent study of military urbanism is entitled America Town, in reference to the gated bar and prostitution district constructed outside Kunsan airbase with the active complicity of South Korean officials and businessmen. What Gillem describes in the greatest detail, however, is the “cultural landscape” of contemporary American consumerism as expressed on a plethora of overseas outposts. This is the landscape that the liberalism of open borders and free financial flows has done everything to create, since the heyday of Reagan and Thatcher in the early 1980s. Gillem’s book is invaluable for helping us to understand how that landscape has been structured by the American version of the developmental planning – namely, military expenditure. Take, for example, the description of Kadena airbase in Okinawa, as seen from a viewpoint in a Blackhawk helicopter:

-

The base, with its sprawling subdivisions, strip malls and streets wide enough to land fighter jets, abutted the compact urban fabric of Okinawa-chi, Kadena-cho and Chatan-cho. The golf course stood ready to defend the base at its western edge. The split-level ranch homes had yards big enough to land several Blackhawks. The main shopping center’s parking lot was bigger than the dense town center of Okinawa-chi. What was the U.S. doing building like this in a place so short of land that airports are constructed on artificial islands? How did this happen and what does this tell us about the culture of America’s military and the complicity of the “host” nation? 7

Here, no doubt, are the most concrete subjective consequences of contemporary U.S. imperialism, now being spread across the world by neoliberal economics. What Gillem has assembled is the portrait of a bloated society living on borrowed money and time, under the shadow of current and impending battles for the ultimate developmental resource: the oil needed to run all those grotesquely oversized cars, trucks, ships and planes. The slick, hedonistic world of contemporary hyper-consumerism has brought on the imminent risk of resource wars.8The title of Johnson’s book, Nemesis, expresses this threatening situation very well, with its reference to the Greek deity of vengeance and retribution for hubris, or overweening pride. But how could he have failed to notice that the Nemesis is also the goddess who cursed the proud young man Narcissus, causing him to fall fatally in love with his own reflection?

Pretty Things that Glitter in the Dark

Here’s another question, closer to everyday experience. Is it possible to see through the cheap façades on which the history and the future of our desires are reflected? This is what siren eun young jung has attempted in a video installation entitled The Narrow Sorrow. She begins with a freeze-frame on one of the tiny doorways barring the walk space between two clubs. The passageway leads back to the lodgings of the Filipino girls who are now brought over by the hundreds to work the strip joints and brothels of Dongducheon. Moving images then begin to appear on the various rectangular spaces: first the gate itself, then the façade of the Bridge Club, the sign of the J.C. Beer Bar Lounge, etc. We see street scenes, construction sites, landscapes and rather ghostly images from the Sangpae-dong cemetery, accompanied by an incomprehensible hubbub of voices and muted music. Towards the end of the video, a woman’s body is wrapped in rough cloth for burial. The soundtrack is actually street noise mingled with the organ music from a service in the local Filipino church. The seduction of twinkling lights forms the subject of an elegiac poem that hangs on the wall nearby the installation.

-

siren eun young jung, The Narrow Sorrow

Artistically and politically, The Narrow Sorrow tries to walk through the eye of a needle, groping for a representation of the lives and struggles of women who are doubly excluded from Korean society, because they are sex workers and because they are Filipino immigrants. Yet at the same time, one learns from a scholarly article that the departure of peasant girls from the countryside to the city has left a wife-gap, which is presently being filled by mail-order brides. “By 2004 approximately 27.4 per cent of rural South Korean men were married to non-Korean women.”9Vietnamese women are particularly prized, because of their Confucian heritage. Behind one out of every four rural façades there are messengers from distant worlds.

The work entitled Driveling Mouth, by Koh Seung Wook, explores the destinies of so-called “Western princesses,” who left Korea in the tow of their G.I. husbands and found themselves within four American walls haunted by memories. Their pictures, in glittering party dress, can now be found on Internet homepages. The video installation invites you inside the darkness of a camouflaged tent, where no time is wasted on the niceties. “No matter how hard I work, I couldn’t see a future ahead,” reads a text panel. “I had to become a hooker, and a hooker’s grandma if I could.” The narrative that unfolds is one of marriage and departure, disappointment and bitterness; and then it is told again, with the same pictures symmetrically reversed, from the viewpoint of an Amerasian boy who was abandoned by his father before his birth. At one point we are told that the nameless dead in Sangpae-dong cemetery are called “whores” by some, “Yankee princesses” by others, or “Sisters of the Korean people” by those who resent the violence of the American soldiers. “But what should I call them?” the text asks. “No, why should I even want to call them?” The drivel that pours from two contemporary figures’ mouths seems to embody the obscenity of all those useless words. But it is also the moist inner life of a woman and a man, leaving a wet stain on clean, pressed clothes.

-

KOH Seung Wook, Driveling Mouth

What emerges from the multiple layers of representation in the Dongducheon project is both subtle sociological investigation and an outpouring of intimate expression, bound inseparably together by the challenge of the future. There may well be a clue here for those who are wondering how to definitively move beyond the attitudes of the 1980s generation, when the democracy movement violently confronted the forces of order on the streets, while the Minjung artists excoriated militarist discipline on their canvases. That step beyond is clearly being taken by contemporary Korean activism, which, curiously enough, has also been seduced by pretty things that glitter in the dark. I think it’s worth noting that the first candlelight demonstrations arose in 2003, with the massive protests against American bases after the deaths of Hyo-soon Shin and Mi-sun Shim under the treads of a U.S. Army tank; and that those nation-wide protests came about spontaneously, at the instigation of an inexperienced youth who spread the idea over the Internet. Here, as in the art exhibition, one might point to the cross-class solidarities of an egalitarian feminism, following the arguments of Seungsook Moon who sees a specifically gendered difference in the forms of political engagement developed by women after the end of the dictatorship. But on the basis of my own experiences in Europe and North America, I wonder if the generational question is not equally important. In a deeply flexibilized economy, where mainstream unions can help vote in a conservative president in reaction against the perceived threat of casualized and immigrant workers who are themselves required by the neoliberal policies of that same president, the impossible and unrepresentable struggles of Filipino club girls could be more relevant to the political landscape than any exclusively working-class tradition would allow us to imagine.

In response to my questions about the aims of the recent protests against the importation of American beef – and against the “bulldozer” approach of the new president – the activist and professor of peace studies, Daehoon Lee, replied that in his view “the people are searching for their soul.” The reason why is clear: in the contemporary period, both political adversaries and political goals are hard to name. Driven by the volatile winds of finance, liberal empire is inherently crisis-ridden; and the chaotic swings of its transnational economy can provoke a conservative return to order at any time, as we’ve seen in the most ugly way in the United States. Under these conditions, the claims of democracy and the rule of law can easily collapse into a state of exception. But it is the ordinary, lawful, democratic functioning of liberal empire that provokes the crises, above all when the endless productivism and consumerism of industrial modernity meets its limits and gives rise to resource wars. How a more sustainable form of society can be found is the ultimate question. The search to articulate political subjectivities with a foundation in personal experience and a consciousness that goes far beyond them is what interests me most today. This articulation isn’t easy, and among other things, it involves changing the definition of what art is and what it can be. That’s almost impossible to do when you have repressive regimes on your back. Yet the shaky footing and extraordinarily poor press of militarism in South Korea, and elsewhere in Latin America and Europe, gives some hope that the worst may be avoided, and that more long-term problems may come to the fore again.10

I said at the beginning, quite naively, that I was looking for an exit from liberal empire, and I still am. But beyond the moment of exodus comes a season of new beginnings. Maybe what’s needed to redefine freedom in our time are 50 ways to find your lover.

-

Demonstrations against US bases, Seoul, 2003

NOTES

1 Sangdon Kim’s video document, Discoplan, was presented along with all the other works I will mention here at the exhibition Dongducheon, A Walk to Remember, A Walk to Envision, curated by Heejin Kim at the Insa Art Space in Seoul, July 16-August 24, 2008. It was previously presented at the New Museum, New York, May 8-July 6, 2008.

2 For documentation, see http://www.16beavergroup.org/korea.

3 Quote from an interview included in the installation by Sangdon Kim, Little Chicago.

4 See Seungsook Moon, Militarized Modernity and Gendered Citizenship in South Korea (Durham: 2005, Duke University Press).

5 For examples, see The Battle of Visions, exhibition catalogue, October 11-December 3, 2005, Kunsthalle Darmstadt.

6 Chalmers Johnson, Nemesis: The Last Days of the American Republic (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006).

7 Mark L. Gillem, America Town: Building the Outposts of Empire (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), pp. xiii-xiv.

8 See Michael T. Klare, Rising Powers, Shrinking Planet: The New Geopolitics of Energy (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006).

9 Charles Armstrong, “Contesting the Peninsula,” in New Left Review 51 (May-June 2008), p. 154.

10 Among recent events, the closure of the American airbase in Manta, Ecuador, and the tremendous resistance against the new facilities in Vicenza, Italy, are worth one’s attention. See http://www.no-bases.org and http://www.nodalmolin.it. For the latest on the planned American megabase in Pyeongtaek, see http://saveptfarmers.org.

No comments:

Post a Comment